LET’S BE HONEST about the genus Callophrys: with a few green exceptions, these aren’t exactly charismatic butterflies.

Known as elfins and green hairstreaks, Callophrys (kah-LOW-fris) butterflies perch with their wings folded closed above their bodies, at which point they become about the size of a penny — and only somewhat more ornate.

The Callophrys have never inspired much poetry or gained any traction on social media. They’ve not been a cause célèbre of demonstrations or protest marches. Nobody’s out there shouting, “Save the elfins and green hairstreaks!”

Except for me because I’ve come to admire the Callophrys as near-perfect insects. Tiny and gossamer, these butterflies embody big and enduring ideas in nature — including human nature.

First is intimacy. Once you locate a Callophrys, perched on a twig or a flower, it will often allow you to approach and sit at length in its good graces. That’s unusual among butterflies. (These animals do have wings, after all.) Sitting with a Callophrys, watching it sip nectar or mate or lay an egg, is a kind of rare intimacy in nature we experience with few other animals. After a while, sure, your Callophrys will depart the scene. But if you’re like me, it will usually leave before you do because it is really hard (even heartless) to turn your back and walk away from one of these little butterflies.

The next big idea is biological diversity. Depending on whose unsettled taxonomy you prefer, at least three dozen Callophrys species inhabit the Earth (perhaps many more), mostly in boreal and temperate regions, including two dozen or so in the Americas and a handful in Europe. Some Callophrys species are generalists, which means the females lay their eggs on a variety of host plants on which the caterpillars can feed and grow. Their varied diets tend to make the generalists more common and widespread among us. Others Callophrys are specialists — their caterpillars can live on a highly restricted diet of one plant species. Nothing else. As a result, specialists can be rare in the world — sometimes exceedingly so.

Regardless of rarity, Callophrys exemplify one of the longest-running relationships in the history of life on Earth: the shared evolution of insects and plants. At its most basic, plants get pollinators and insects get food, including flower nectar for adult butterflies and leaves for growing caterpillars.

Butterfly caterpillars generally prefer angiosperms, the abundant and diverse plants we know and love — asters, violets, clovers, grasses, oaks, and countless other species that produce flowers, seeds, and fruit, and whose leafy greens make for soft and nutritious caterpillar food. But some Callophrys go for gymnosperms, the evergreens — pines, spruces, cedars, and their ilk. A diet of conifer needles is rare among butterfly caterpillars. And this unusual bond between some Callophrys and evergreens is perhaps my favorite thing about these tiny butterflies because it exemplifies my third big and enduring idea: a sense of place.

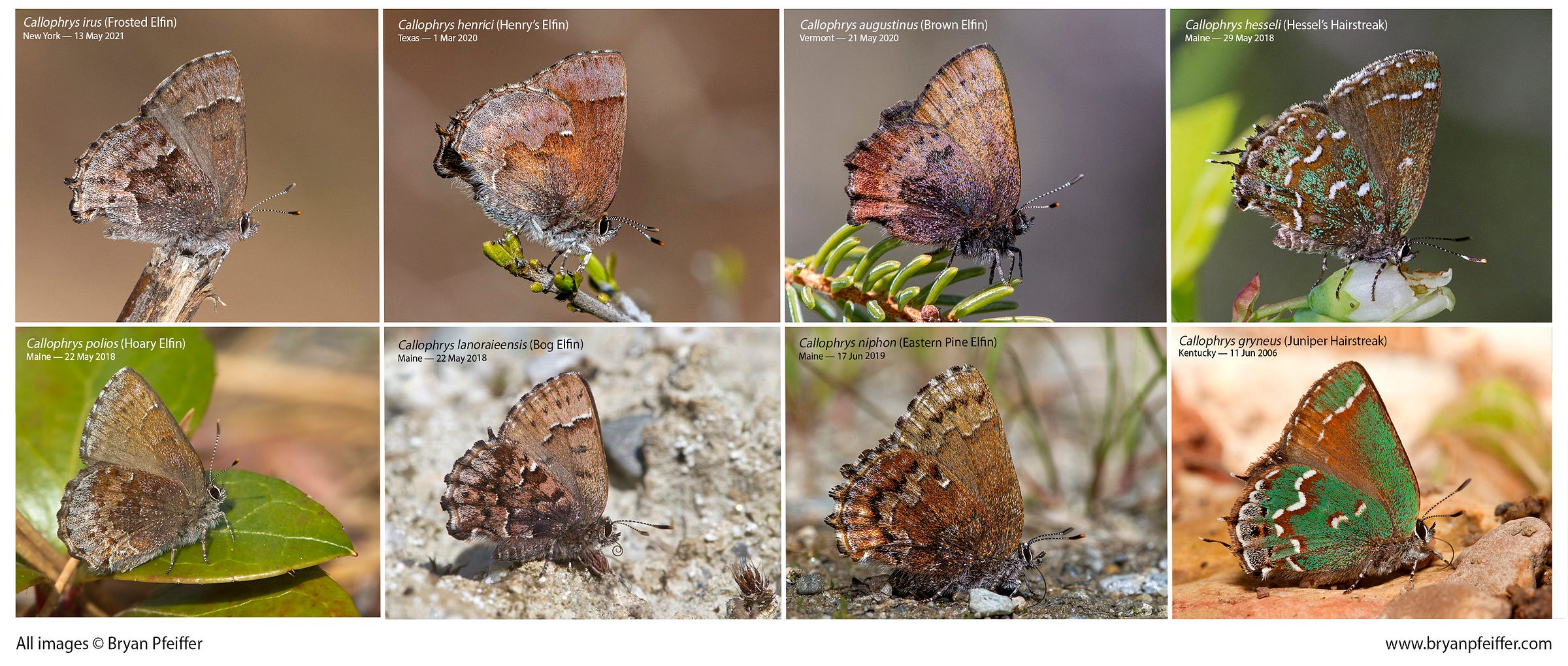

Hessel’s Hairstreak (Callophrys hesseli), for example, lays its eggs on Atlantic White Cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides) — and on no other plant in the world. You might find Atlantic White Cedar and no hairstreaks, but you will never find a Hessel’s Hairstreak far from that tree. I have had the good fortune to find the butterfly and its cedar together across the full extent of their shared range — a coastal and inland swath of territory running from the Gulf of Mexico to southern Maine. Where most people might see on a map the sprawling U.S. megalopolis known as the Eastern Seaboard, I see the only place on Earth where a lovely green butterfly can meet up with its indispensable tree. (That’s a Hessel’s Hairstreak upper right in the montage above.)

A Butterfly is a Bog

Closer to home, literally and personally for me, one of the most elusive butterflies on the continent, Bog Elfin (Callophrys lanoraieensis), lays its eggs exclusively on Black Spruce (Picea mariana) in woodland bogs scattered nowhere else in the world but northern New England and adjacent Canada. Even at the relatively few bogs where it is known to live, Bog Elfin is basically unknown. Our tiniest elfin, smaller than a penny, it flies as an adult for only about two weeks from mid May to early June. That’s it. The rest of the year, a Bog Elfin lives on Black Spruce boughs as either an egg, a caterpillar eating spruce needles, or a chrysalis (the form it takes over winter) — all of which are virtually impossible to find.

Generation after generation of Bog Elfins never willingly leave their bog. The bog is their community, what ecologists call a “natural community.” And as a community, a bog is more than the sum of its squishy mat and scattered trees and shrubs, its suite of birds nesting, and its black flies out for blood. Bogs exist or do not exist because of bedrock and glaciers, latitude and longitude, weather and climate, and lots of other conditions and forces, not the least of which is humanity in all its manifestations — anything from a chainsaw to a 66-year-old biologist and writer walking around on a gimpy knee and carrying a butterfly net and an outsized fondness for little brown butterflies. A bog community, like a human community, is an idea and an experience — with history, culture, and destiny.

As it turns out, my home state of Vermont has 97 different kinds of natural communities, each distinct and defined and repeating across the landscape when and where past and present conditions are just right for them. (Your state or province or nation has its own suite of natural communities, which ecologists there might have formally or informally described.) We put names on these natural communities so that we can know more about where we are in the world and what to expect when we’re there. A natural community is a synergy that gives us reason, meaning, even story.

A little Callophrys butterfly is really no different. To my mind, a Bog Elfin is its bog. As a caterpillar, it eats only Black Spruce needles. As an adult on the wing, it sips the nectar of rhododendrons, leatherleaf, blueberry, and other bog flowers. A Bog Elfin is made entirely of bog — and everything that conspires to be a bog. Nothing else. And maybe that’s all the story I need.

More than a reclusive little brown butterfly, a Bog Elfin is an embodiment of its community and a monument to its place on Earth — from the glacier that helped make the community a bog in the first place to the hot-pink orchids that drop me literally to my knees.

A butterfly the size of a penny, on the wing for but a few days, unwittingly tells me where I am in the world. When we sit together on the bog, the butterfly and me, I am home — with a sense of place and belonging more absolute than anywhere else on Earth.

And yet when my human community beckons, when I must take my leave from the bog, you can bet that I won’t turn my back on the butterfly and walk off — not until the elfin flies away first.

Virtue in a Little Brown Butterfly

An essay about my discovery, after 21 years of searching, of Bog Elfin in my home state of Vermont — the first time it had been encountered here. (Through it all, I never lost faith, although I joked that I'd find this butterfly or die trying.) This is in some ways my origin story and manifesto.

Postscripts

There are lots of wonderful things to be said and learned about seeing the world by way of natural communities. The definitive reference here in Vermont, for example, is Wetland, Woodland, Wildland by Elizabeth H. Thompson, Eric R. Sorenson, and Robert J. Zaino.

Below is my montage of elfins and green hairstreaks of the eastern U.S. with names, locations, and dates. By the way, lepidopterists, who generally aren’t Latin scholars, pronounce Callophrys various ways (kuh-LAH-fris, for example, or cuh-LOW-frees) so don’t worry too much about whether your mind recited it correctly.

Finally, for my European readers, by far your most common Callophrys is rubi, commonly called Green Hairstreak. (Stunning photos at Butterfly Conservation.)

Annie Proulx, no stranger to Vermont, has written a sweet little book titled “Fen, Bog & Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and Its Role in the Climate Crisis.” One little quote: “Time shows us the earth as a fluid patchwork constantly in flux so slow it is invisible. Centuries and millennia are the hours and days of a bog.” I sense, Bryan, when you are in a bog you are attuned to kairos time, not chronos time, to the hum of cosmic rhythms and not the tick, tick, tick of the human clock.

A butterfly IS a bog. Much like a fiddler crab IS a marsh. Love how you connect sense of place. It’s so important!