Charles Darwin has gone missing — and I fear the worst.

No, not that Charles Darwin, who is by no means missing from his place of burial in the nave at Westminster Abbey. I refer instead to a jumping spider with big eyes who had taken up residence with me this winter.

In our time together, this tiny spider embodied big ideas about evolution, intimacy, and impermanence. Yeah, all that from a spider about the size of the letter “o” on this page (a bona fide itsy bitsy spider).

But before exploring those weighty matters, I should point out that I almost never assign names to wild animals, preferring to study and enjoy them without any need for anthropomorphizing. This spider’s proper given name is Attulus fasciger, or Asiatic Wall Jumping Spider to most of us. (In those rare instances when I do assign a human name, I typically invoke either Darwin or Rachel Carson — among the most heroic biologists who ever lived.)

I have never named, for example, a domestic house fly or a squirrel in the backyard, although each is no less worthy of our regard. And yet jumping spiders … okay, I’ll admit it: they’re endearing, even to folks who are unsettled by spiders. Their charm emanates not only from those puppy eyes (among eight eyes in total). It comes as well from a jumping spider’s jaunty mannerisms and acrobatic leaps, reminding me of an exuberant child navigating a playground (except that the spiders stick the landing). And as you’ll see below, some of these spiders are ornate and flamboyant beyond belief.

Jumping spiders (in the family Salticidae) jump nearly everywhere on Earth except the polar regions — more than 6,000 species in total. They are almost certainly jumping near you. Rather than spinning webs, jumping spiders use acute vision to spot and then leap to seize prey. They also leap to escape becoming prey themselves (or to avoid the proximate investigations of a field biologist who writes Chasing Nature).

Charles came into my life in December, tempting fate among my small colony of potted carnivorous plants. Day after day, I remained convinced that he’d end up as plant food, most likely in the grip of one of my Venus Flytraps. Day after day, I was wrong. Charles skirted the fringes of the flytraps, never once triggering a jaw to clamp him into oblivion. He scampered easily along the sticky tendrils of my two sundew species. And never did he venture into the death chamber of my tiny pitcher plant. As a result, he became somewhat reliable — a destination for me each morning. I’m reluctant to say it, but Charles became a companion.

In truth, however, Charles had no regard for me, except perhaps wariness of me as a potential predator. But my own odd notion of our companionship became apparent to me on the morning of December 19. Having not seen Charles for six consecutive days, I had assumed he’d perished. (By the way, I had earlier resolved to intervene on Charles’ behalf for only two reasons: if I myself had startled him into the trap of one of the carnivorous plants, and to raise fruit flies for him to catch, kill, and eat.)

After my breakfast on the 19th, and still assuming he was gone, I nonetheless perused his former haunts. This had always required diligence on my part — basically a search for a spider resembling a speck of soil or dirty perlite among my three pots of plants. After a minute or two of my unsuccessful scrutinizing, suddenly there he was in plain view atop a leaf of my pitcher plant, gazing up at me as if to say: “WTF are you looking at!” Yeah, complete anthropomorphizing on my part; I was elated nonetheless. “Charles is back!” I wrote in my journal that day.

So what shall I make of my spider teacher? To be sure, we humans are hard-wired to nurture creatures with big eyes and cherubic features — our own offspring. We’ve probably selected for similar traits among puppies and kittens. Our affinities for those characteristics, however, are misplaced among giant pandas, leopard seals, and jumping spiders. Those big eyes did not evolve to trigger any empathy in us — or even parental care on the part of jumping spiders. Those big eyes instead allow a jumping spider to be a ruthless predator upon tiny insects — and to be a survivor. That’s about it.

Still, those eyes offer plenty to me. When a jumping spider turns and fixes his gaze upon me, even to size me up as a potential predator, when my two eyes meet his eight, the spider and I become aware of one another. And at that moment, I have come face-to-face with millions of years of evolution by means of natural selection — and perhaps more so with the human capacity for wonder.

Jumping spiders have a 50-million-year head start on human beings here on Earth. They’ve been places, seen things. When they first showed up, dinosaurs were a recent afterthought. And these spiders will almost certainly do fine once the brand new ape known as Homo sapiens is gone for good.

Still, I’ve got at least one thing on this doe-eyed survivor. When a jumping spider unwittingly comes into my life, I can stop and observe. I can contemplate not what’s next, not what’s online, but what’s alive and wild and genuine in front of me — no matter where I am.

And maybe that’s all I need from Charles. Companionship? Intimacy? Notions of impermanence? I don’t know — maybe. But I do know one thing.

Why do I seek out a jumping spider?

Because he’s there.

Epilogue

My last encounter with Charles was on December 25th, before I left home for a week of travel. I haven’t seen him since returning home on New Year’s Eve. Although I failed to raise fruit flies for him (it’s winter here in Vermont, after all), I suspect Charles had found tiny insects on his own to eat among my plants. I recognize he may now indeed be gone for good. Hey, death happens to the best of us — and to everyone we love. So there is yet another reminder, from a tiny spider no less, for us to make the most of every breath, every moment.

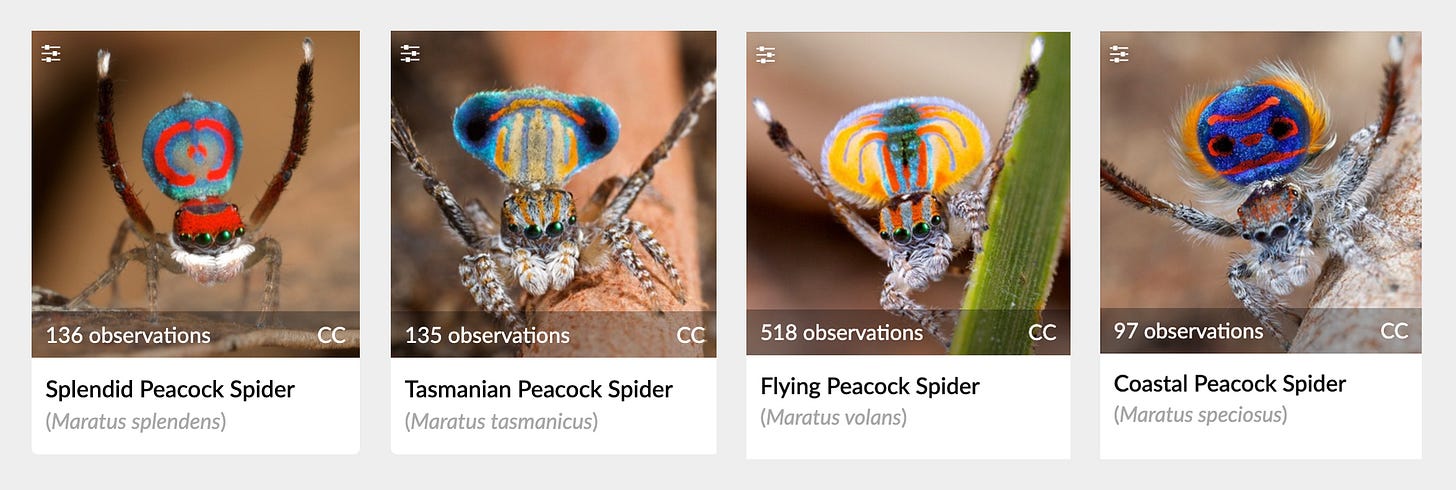

Jumping Spiders Known as Peacock Spiders from Australia

Postscripts, Images and Video Links

As you might have suspected, the Asiatic Wall Jumping Spider is not native to North America. The species perhaps arrived on imported Asian goods. Or it very well could have traveled by “ballooning.” That’s when spiders float on strands of silk, catching air currents that can transport them great distances, including across oceans. (Although they don’t construct webs, jumping spiders can leave behind a lifeline of silk in case they miss the landing or need to retreat.) Since its arrival, the Asiatic Wall Jumping Spider has spread in part by colonizing our walls, and probably finding prey attracted to lights.

If you like that montage above, you must at least scroll through Jurgen Otto’s gallery of peacock spiders. Or watch some of Jurgen’s videos. When you do, you will understand why I must travel to Australia before I leave this Earth. (Another reason to go is birdwing butterflies, but that’s for another post.) And remember: these spiders aren’t much bigger than a grain of rice.

Finally a few more shots of Charles: on a Venus Flytrap (Dionaea muscipula), on a Cape Sundew (Drosera capensis) with a dime, on a Fork-leaved Sundew (Drosera binata), and being a wall spider on a terracotta pot.

I've anthropomorphized my fair share of animate and inanimate objects over the years. This post made me wonder if they entomorphize us?

I think this community of Bryan fans should CROWD-$$OURCE A TRIP TO AUSTRALIA for Bryan!!!!!!!!!