A Parasite, Clickbait and Honesty

Virtue from a Flatworm that Lives Inside Bird Guts and Snail Eyes

IN THE battle waged online for your attention, it would have been easy for me in this essay to go with “zombie snails.” Or maybe “brain-hacked suicide snails.” After all, those are common tropes in internet posts about the flatworm unceremoniously named Green-banded Broodsac (Leucochloridium paradoxum), which makes a snail’s eyes resemble an insect larva (or in internet parlance a “bizarre pulsing disco show”).

For clicks and likes, this kind of baiting might have been expected of me, perhaps even excusable. But it would have been a disservice to the snail, to the parasite, and certainly to you. We’re better than that. (We are, right?)

So instead I bring you a genuine story about how I spent my summer vacation with a parasite that lives inside a bird’s cloaca and a snail’s body. It's a tale of how I discovered the flatworm in my own community and soon became obsessed with learning about it. It is sincerity from the earth. Because if the world needs anything right now it is rectitude, not exaggeration and clickbait, especially when it comes to the diversity of nature and the complexities of evolution.

A Most Vivid Parasite

The first thing to know about this flattened, tiny worm — a trematode — is that it does not live free on its own in the outdoors. The flatworm spends the entirety of its adult life inside a bird’s intestine or cloaca, which is where waste and either sperm or eggs are passed out of a bird’s body.

The only way and form in which the trematode gets outside is when it produces eggs, which are then delivered to the free world by the bird in its droppings. Yep, the adult flatworm lives in bird guts and its eggs live in shit. (Think about that next time you’re stuck at the office.)

The vast majority of those eggs, I suspect, dry up and perish wherever bird droppings land — end of the line for a flatworm. Except when an amber snail in the family Succineidae crawls along and … well … eats shit. It’s a way of life for this parasite: only within a snail can the trematode continue its lifecycle. The snail is the parasite’s essential intermediate host. And this is when things get interesting.

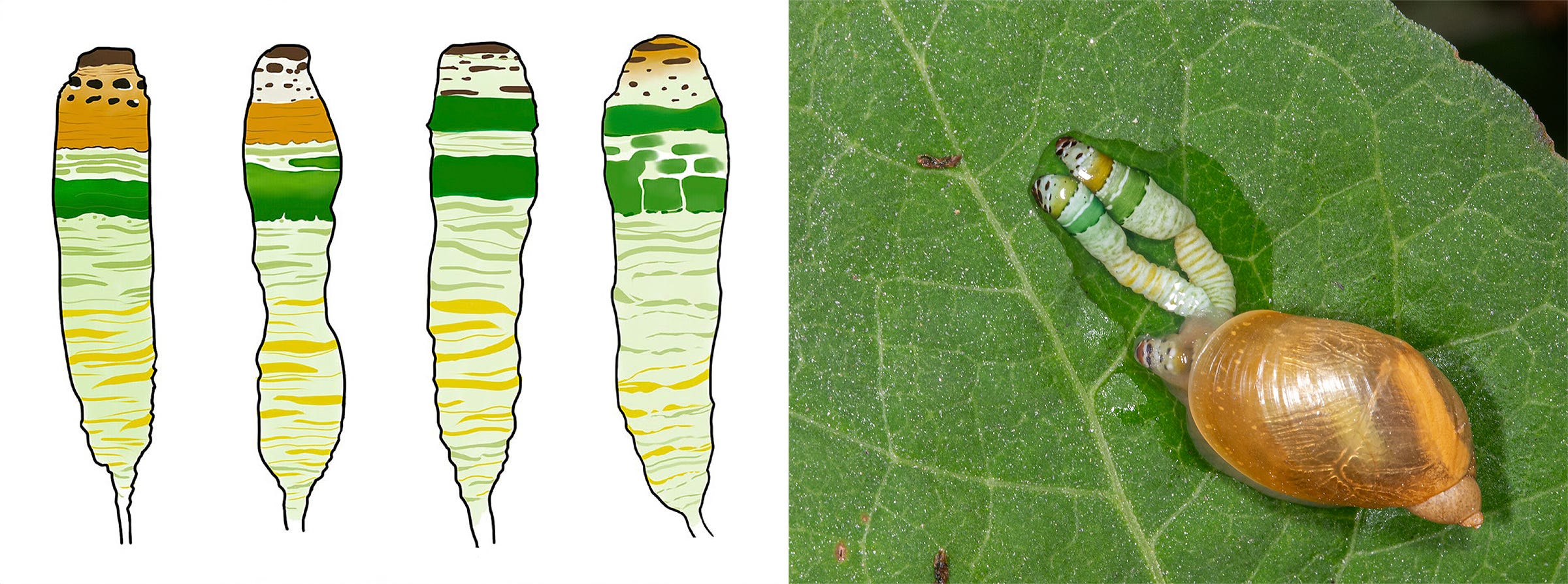

Once inside a snail’s gut, the flatworm’s eggs hatch to release elongated, hairy larvae (called miracidia), which are now free to move about the snail’s body. There the hatchlings continue to develop, but now within a new accessory: a colorful, sausage-shaped chamber called a broodsac. The broodsac acts like an ornate, pulsing, living entity in its own right. And its destiny is to get itself and its trematode larvae back into a bird’s gut.

The snail is the ride. Except that songbirds generally don’t eat snails. They prefer fruit, seeds, and insects. But the broodsac is banded and flecked with pigments that make it resemble a moth or butterfly caterpillar (and to some extent a sawfly larva) — good eating for a bird. So the broodsac duly makes its way to the snail’s head and then into the eyestalks, wherein it pulses in an odd and wonderful spectacle that presumably attracts the attention of birds (and the internet). It’s quite a show.

Once a bird takes the bait, the broodsac’s larvae go on to mature into adult flatworms in its intestine or cloaca, ultimately producing trematode eggs — a lifecycle complete. All good … except for how it plays online.

The Flatworm, the Internet and Us

The broodsac certainly got my attention, pulsing in my direction as I botanized during a walk with my pup Odin in a park in my home city of Montpelier, Vermont. It was at 7:58 AM on 9 July 2024. (My life hasn’t been the same since.)

At the time of my discovery, other than suspecting some sort of invasion of the snail, I’ll confess to not knowing what the heck was going on. Only after consulting with a few naturalist friends and colleagues (one of whom was immeasurably envious of my find) did I begin to learn about the nature of this parasite — and the culture of the internet that distorts it. (National Geographic Society, which ought to know better, is among the offenders.)

Eager to learn more, in the days after my discovery I searched my city for more occupied snails — without success. Until my initial encounter, the parasite had only been reported (to GBIF and iNaturalist) and positively identified 11 times in all of North America. (It’s more common in Europe and Asia.) I nonetheless kept searching. Four days later came my triumph: a population of amber snails only a short distance from my home, roughly (very roughly) one in 50 of which were displaying parasites. I now had a study site (although I admit this was more entertainment than study for me).

I visited with the snails regularly, brought some home for observation, took lots of pictures and video. I felt kinship with Carl Jørgen Wesenberg-Lund (1867-1955), a Danish zoologist who studied the parasite and the snail, publishing an exhaustive 69-page treatise (Wesenberg-Lund 1931). (Like most of us, Carl could have used an editor.) All the while, I have to say, I was dazzled by an organism in my neighborhood that only days earlier I had never known existed. Nature’s like that — full of opportunity, even among parasites.

Rather than recounting the details of my investigations, I’ll take issue with internet distortions of the parasite. First, it’s easy (and somewhat gratuitous on my part) to nitpick the zombie metaphor. In fact, these snails are not soulless, walking crawling corpses whose bodies have been overtaken by some sinister spirit or force (flesh-eating or otherwise). Admittedly, anything zombie plays well in the zeitgeist these days. (I myself even deployed it leading up to this post — shame on me.)

Next, the parasite supposedly manipulates the snail’s behavior, forcing it to crawl up and out into the open on plants leaves where it can be more easily spotted and preyed upon by songbirds. It’s often described online as the parasite’s exerting “mind control” over the snail — or that the poor snail is “hypnotized” and “doomed to follow the parasite’s will.”

Be wary of this kind of language online relating to nature. I’m not sure how to read a snail’s mind — or that anyone in fact has. (I wish I could.) Nor does anyone, I presume, know that a parasite larvae is capable of exercising such willful mind-control. We need not confer sinister intent on the part of the parasite or victimization on the part of the snail. That’s anthropomorphizing. To be sure, there’s a role for metaphor in explanatory science and nature writing. But the pitched battle for attention online too often sends science writing into speculation and excessive drama.

Do the snails move higher and to more exposed spots? Absolutely. At dawn on dewy summer mornings at my study site, lots of amber snails, occupied or not with parasites, would routinely ascend from the soil — usually less than a meter or so — to sit on plant stems and leaves. The parasitized snails among them climbed higher than others and were plainly more visible to me (presumably to birds as well). I had noticed this even before reading about it in published scientific literature (or online for that matter). And it’s been well documented by researchers working in Poland (Wesołowska 2013).

Mind control? Maybe. Or maybe those snails, their eyestalks occupied and blocked by pulsing broodsacs, simply went higher in order to better see or sense or otherwise experience the dawn light. Nothing sinister about it. We could even speculate that it’s the snails running the show here, climbing higher and exposing themselves so that birds will come along and pluck those broodsacs from their eyestalks, which the snails reportedly can then regenerate. To be sure, there are well-known examples of parasites manipulating animal behavior. We just need to be cautious on the mechanisms.

Once the summer sunlight struck my snail population each day, virtually all of them, including the occupied snails, retreated for cover beneath leaves or to soil, even as Gray Catbirds, Red-eyed Vireos, Song Sparrows, and other putative broodsac predators fed nearby on genuine insects. Not incidentally, outside of the lab, there is scant evidence of birds preying upon the boodsacs in the wild. Apart from one oft-repeated clip online, few people in the world have actually seen it. I aim to see it next year.

I’m no parasitologist. No matter. Whatever the case, to my mind this is a parasite being a parasite, a snail being a snail, a bird being a bird — intrinsically worthy without dramatization on our part. In the intersecting lives of the flatworm, the snail, and the bird, I need no ominous music or manipulative prose. In nature, all I need is exuberance, curiosity, and an open mind.

Postscripts, References and Clickbait

Summertime is the season for these snails and parasites. Here’s an iNaturalist map of 179 Research Grade records of Green-banded Broodsac around the world, mostly in Europe.

The broodsac’s behavior goes by the term “aggressive mimicry” — an organism resembling another either to lure in prey or, in this case, to itself become the prey.

I’m not sure which snail species is involved here. The trematode is often reported in the species Succinea putris (Common European Amber Snail). The abundant North American amber snail species is Novisuccinea ovalis (Oval Amber Snail).

Casey, S., Bakke, T., Harris, P. et al. 2003. Use of ITS rDNA for discrimination of European green- and brown-banded sporocysts within the genus Leucochloridium Carus, 1835 (Digenea: Leucochloriidae). Syst Parasitol 56, 163–168 (2003). doi.org/10.1023/B:SYPA.0000003809.15982.ca

Doherty JF. 2020. When fiction becomes fact: exaggerating host manipulation by parasites. Proc Biol Sci. 2020 Oct 14;287(1936):20201081. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.1081. Epub 2020 Oct 14. PMID: 33049168; PMCID: PMC7657867.

Nandy, G., et al. 2022. Infestation of sporocysts of parasite Leucochloridium in the snails Succinea daucina and Indosuccinea semiserica. J. Environ. Biol., 43, 722-726 (2022).

Robinson, EJ Jr. 1947. Notes on the Life History of Leucochloridium fuscostriatum n. sp. provis. (Trematoda: Brachylaemidae). The Journal of Parasitology, Dec., 1947, Vol. 33, No. 6, Section 1 (Dec., 1947), pp. 467-475 Downloaded from 132.198.50.13 on Sun, 25 Aug 2024 14:15:32 UTC

Usmanova, RR, et al. 2023. Genotypic and morphological diversity of trematodes Leucochloridium paradoxum. Parasitol Res. 2023 Apr;122(4):997-1007. doi: 10.1007/s00436-023-07805-7. Epub 2023 Mar 6. PMID: 36872373.

Wesenberg Lund, C. 1931. Contributions to the development of the trematoda Digenea. Part I. The biology of Leucochloridium paradoxum. K. danske Vidensk. Selsk. Skr., nat. mat. Afd. 9: 89–142.

Wesołowska, W. and Wesołowski, T. 2013. Do Leucochloridium sporocysts manipulate the behaviour of their snail hosts? Journal of Zoology. 292. 10.1111/jzo.12094.

(All of this work informed this post, although not all of it is cited above.)

If I subscribe, does that make you my host?

I can’t stop thinking about this