To hear it from the anthropologists, we humans are drawn to wide open spaces because they make us feel safe. Prairies and meadows (perhaps even our oversized lawns) supposedly echo the African savannah, where our early ancestors could more easily spot hyenas, rhinos, saber-toothed cats, and other predators.

All that may be true. But I myself was drawn to the American savannah for another reason: an extraordinary butterfly. I stayed for songbirds, wildflowers, and a disturbing lesson in safety, heartbreak, and extinction.

But first let’s get one thing straight about the butterfly, which is called Regal Fritillary (Argynnis idalia). When you first lay your eyes upon a Regal Fritillary, you may decide to quit your job, sell your house, become a lepidopterist, and devote the rest of your life to this imperiled insect. (By the way, it’s pronounced “FRIH-till-air-eee” here in North America and “frih-TILL-uh-ree” in European English.)

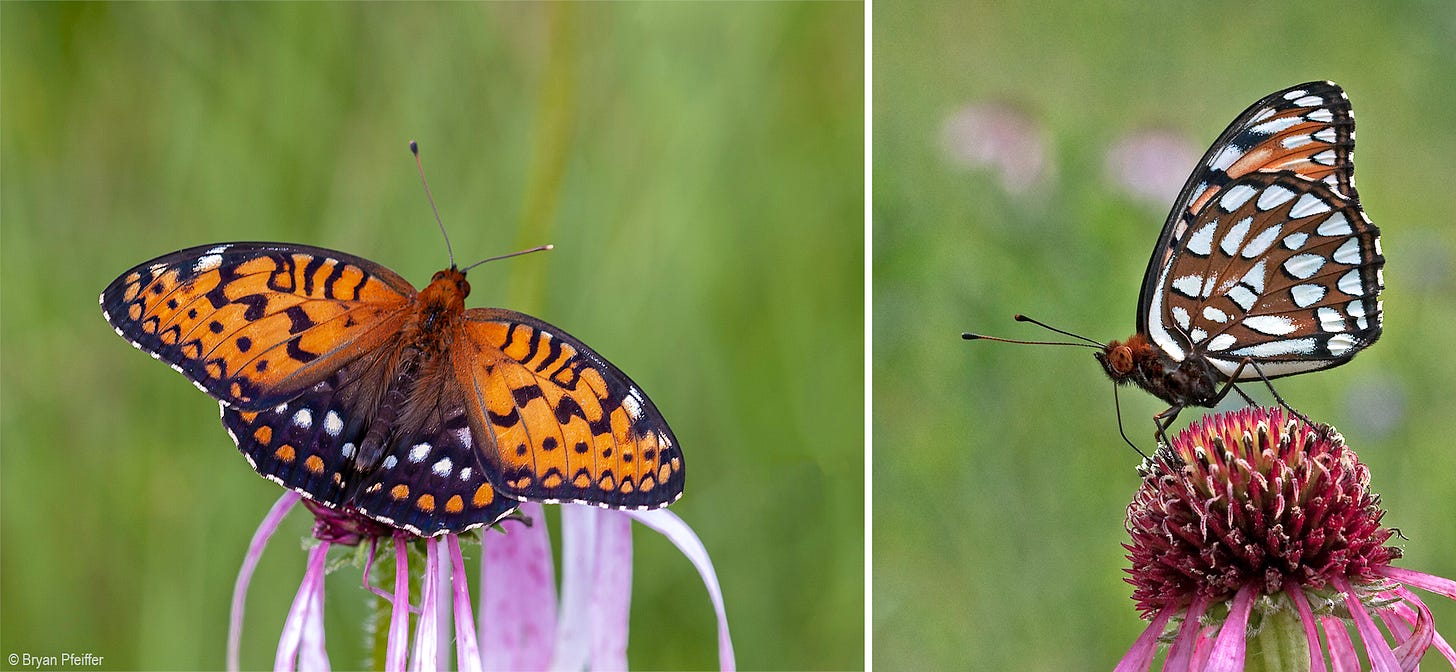

The Regal is like no other fritillary, even its close relatives, most of which display golden-orange wings with variegated black speckling. I mean no disrespect whatsoever toward these “ordinary” fritillary relatives, but theirs is a somewhat common butterfly wing pattern. The Regal, magisterial and well named, shows blood-orange forewings and darkened hindwings marked with rows of orange and or white spots. And that’s only half its resplendence.

Dancing in flight across the prairie, the “Regal Frit” is big and flashy. When it stops to sip nectar from a wildflower, this butterfly offers one of the most indulgent experiences I know in all of nature. (And trust me, I know indulgence in nature.) The Regal either flaunts those bold uppersides or folds its wings above its body to reveal outrageous undersides: pearly, slivered spots on dark-chestnut hind wings, which themselves are set against the soothing, peach- or mango-colored flip-side of the forewings. Graced with either view, no self-respecting human being can turn and walk away from this butterfly.

I’d compare the incomparable Regal Fritillary to the American Bison (Bison bison) except that there’s a European Bison (Bison bonasus) as well. But you get the idea, especially because the butterfly and the bison at one time shared wide open spaces across the American prairie. Then things went bad for both. First we slaughtered the bison, and then we destroyed the prairie. Regal Fritillaries were among many casualties. Still persecuted, still in decline, the fate of this magnificent butterfly remains uncertain, especially so in the eastern United States, where the Regal Fritillary’s last stand is a 457-acre combat zone. And I do not mean combat zone figuratively.

Regal Frits historically flew among scattered prairies, meadows, and other openings across portions of the East, including in my home state of Vermont. And let’s get one thing straight about Vermont: it is a state of exalted beauty, sanity, and decorum in a nation of big-box homogeneity, landscape destruction, and political disfunction. Although Vermont remains a great and, as we like to say, “brave little state,” it is not the same state without Regal Fritillaries. No state is. To know heartbreak is to have tracked down some of Vermont’s remaining Regal Fritillaries—not floating across meadows but instead residing as specimens on pins in museum collections.

The only reliable place to experience Regal Fritillaries in the eastern U.S. is that combat zone—Fort Indiantown Gap National Guard Training Center in Pennsylvania, where you might also experience sniper and machine-gun fire, tanks and their ballistic weaponry, grenade and artillery explosions, and major troop movements. But let’s get one thing straight about military bases and training grounds: although warfare is deadly to virtually all living things, it turns out that the Department of Defense owns some vital wildlife habitat here in the U.S., especially native grasslands. (Hey, there’s no suburban sprawl, industrial agriculture, or mega-shopping malls on these sites.) Sometimes the DOD strives to protect rare wildlife on its properties. It’s true. I myself have been employed to investigate birds and insects at military sites. (Incidentally, it’s important to let the people in command know that you’re out there working in the woods or on the prairie so that they don’t accidentally shoot or drop a bomb on you; I am not joking about this.)

Although there’s a worthy effort to save the fritillaries at Fort Indiantown Gap, it may not be enough. In the lame-duck days of the Biden administration, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) issued a proposal to protect the Regal Fritillary, with the eastern population at the fort to be listed as “endangered,” which means at risk of extinction in the foreseeable future. USFWS also proposed listing the rest of the Regals—declining and scattered across 14 states—as “threatened” with extinction.

Fourteen states might seem like a lot. But this hardy butterfly once flew in 32 states. And its prospects aren’t improving. By now, you probably know why. First and deadliest is the historic and continued conversion of grassland or other suitable habitat, especially tallgrass prairie, to agriculture. It obliterates or fragments the essential communities of plants that nurture these butterflies, most notably the native violet species (Viola spp.) that fritillary caterpillars eat exclusively in order to grow. Where there are no violets there can be no fritillaries. Other threats to prairie sites and their butterflies across the Plains and West include farmland herbicides (which kill violets and plants used by adults for nectar) and insecticides (which kill insects), drought, invasive grasses, woody plant encroachment (succession), occasional fire, and periodic haying or grazing by livestock.

With those threats persisting, the fate of the Regal Fritillary now depends on scientists, volunteers, landowners, and conservation groups working to save this impressive insect. It depends as well on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Endangered Species Act, whose effectiveness the Trump administration is plotting to subvert. It’s hard for me to imagine Trump’s secretary of interior, Doug Burgum, acting to protect a butterfly (although I remain open to the possibility that he and USFWS might do right by these insects).

On Not Finding a Regal Fritillary — and a Vision

Meanwhile, it had been 16 years since I myself had witnessed Regal Fritillaries—each a year of longing, each a fading of butterfly light. So during a visit with family in the Midwest around the Summer Solstice, I made a pilgrimage to the 8,400-acre Kankakee Sands preserve in Indiana, where Regal Fritillaries fly at a prairie restored by the state’s chapter of The Nature Conservancy.

Away from the preserve, the landscape of northwestern Indiana and so much of the fritillary’s lost homeland can perhaps be described in three words: corn and corn. Well, okay, maybe that’s unfair. A more nuanced version would be: corn, corn, soybeans, wheat, and livestock. For thousands upon thousands of square miles, a prairie butterfly doesn’t stand a chance.

Kankakee Sands, an ambitious grassland restoration on TNC’s part, is like planting a tree in a clearcut, like playing cello in a bombed-out city—a small act of hope in what remains of the fritillary’s range across the Great Plains and West. (Hey, even Republicans might like this restoration project because it amounts to a private landowner [TNC] doing what it pleases with its property.)

But here’s the thing about my visit to Kankakee Sands: during two days of searching the prairie, I did not encounter any Regal Fritillaries. None. Not that the butterflies are gone from this preserve—far from it. So perhaps I simply blew it and overlooked the frits? This is doubtful because I’m good at finding butterflies. More likely is that I came to the prairie a few days too early this particular year—before the adult males, on the wing earlier than females, had emerged from their chrysalises to take flight for the season. I nonetheless made the best of each moment at the preserve: Dickcissels and Henslow’s Sparrows issuing their odd, staccato songs; saddlebag dragonflies drifting overhead; prairie wildflowers in bloom; and my meeting up with four friends who live in Indiana.

Still, something wasn’t right on the prairie. I cannot shake the notion that I foresaw and experienced a dark and dreadful future. As it turned out, I encountered relatively few butterflies of any kind during my visit. Too many of the prairie’s wildflowers were virtually barren of butterflies and other nectar-seeking insects. That even included the blaze-orange Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa), whose nectar so many insects find hard to resist. The prairie did not glow in its usual butterfly light of azure, copper, carmine and countless other hues. (Examples below.) It was troubling—and yet sadly not surprising.

To be sure, insects can experience normal boom-and-bust swings in local abundance; so I will not draw firm conclusions based on what I did or didn’t see during only two days at the prairie. But one thing is clear: the outlook for butterflies and many other insects is already dismal. We’re losing them, their astonishing diversity and abundance. Take, for example, a recent study, published in the journal Science, finding that during the first two decades of the 21st century, butterfly abundance across the contiguous United States dropped 22 percent among 554 species. The decline was rapid, relentless, and occurring in virtually all regions of the country. (I wrote about it in an essay titled “The Problem with Butterflies.”)

Not long ago, troubling news from the natural world was just that — news. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, for example, and

’s The End of Nature grabbed us by the lapels and shook us into action. Scientists and writers and activists fostered social movements. Now the warnings and reports seem all too common and routine—heartbreak after heartbreak rolling through news cycles that invariably waste our time with distraction, celebrity, and puffery.As for me, not seeing butterflies on the prairie was an odd source of distress, as if I was witnessing a terrible vision: landscapes damaged and depauperate, children who do not know wrens or orchids, military bases as sanctuaries, a planet losing its diversity and beauty, a future bereft of nature. A future none of us wants. A fate we might yet avert.

As the anthropologists tell us, we’re drawn to the prairie to feel safe from predators. Yet the prairie itself is not safe for all living things. We are now the predators. And if we can’t even make the world safe for butterflies, our most enchanting of insects, then how can any of us truly be safe in a prairie—or in countless other sacred and wild places on an increasingly damaged planet?

The Problem with Butterflies

Their beauty and grace alone would seem to warrant at least some measure of loyalty and reciprocity on our part. And that is to say nothing of how they’ve become iconic in our culture—from poetry to jewelry, spirituality to tattoos. So by now you’d think we would have found a way to get along with butterflies.

Two Minutes of Regal Bliss Courtesy of Dan W. Andree

References

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service). 2023. Species Status Assessment Report for the Regal Fritillary: Eastern Subspecies (Argynnis idalia idalia) and Western Subspecies (A. i. occidentalis). Version 1.0. 288 pp.

Regal Fritillary Federal Listing Proposal: Federal Register / Vol. 89, No. 151 / Tuesday, August 6, 2024 / Proposed Rules

The best answer, if it can happen, is to educate children in the classroom and outdoors. Build the fascination and interest from a young age. When they grow up they may care for natural habitat. It’s just a small idea though, against big agriculture.

Based upon my experience (admittedly anecdotal and not scientific), the purported percentage decline in butterflies seems like an underestimate. It is heartbreaking.