Honoring Dead Butterflies

From lifeless insects on pins, lessons for the living. But are we worthy?

AMONG MY MOST TREASURED of gifts this winter has come to me by way of a thrift shop in Belfast, N.Y.: a cache of 528 butterflies mounted on pins and arranged in old wooden display cases with glass tops.

It might have been easy for someone else to toss the butterflies and keep the cases. I care more about the butterflies. After all, as an entomologist I routinely spend a portion of my winter in the company of dead insects — millions of them.

Biological specimens like these, housed largely in academic museums, have for centuries been the currency of scientific discovery and research. They also constitute a kind of Rorschach test. Some people see only death or the human proclivity for collecting and displaying things. Others see a kind of taming of nature or even artistic expression in the tidy arrangements.

These 528 butterflies may be all that. But my now owning them comes with an obligation: to honor the dead for what they have given us, and to see to it that these specimens assume their rightful place in our body of scientific knowledge.

First, however, on an otherwise routine winter day, from the comfort of my office in Vermont, my mind traverses the continent on the wings of these butterflies.

A Red-banded Hairstreak, marked not with a band but rather a crimson lightning bolt, transports me to Palmetto, Florida. A Juba Skipper darts and flashes pert white markings in the mountains north of San Francisco. And a small, orange-and-black butterfly named Harvester beckons me to an alder wetland in central Pennsylvania.

Although I do not know entirely the provenance of these butterflies, each specimen’s pin bears one or two tiny, white rectangular labels inscribed with a date and location of its collection from the wild, along with its given scientific name. That’s data — valuable to science.

The oldest specimens date back to 1952, before the word biodiversity came to our lexicon and the extinction crisis to the zeitgeist. So perhaps among them are butterflies that no longer live where they once did or may now be endangered — not because they were collected for science but rather because habitat destruction, industrialized agriculture, the climate crisis and various other environmental hazards are driving insect diversity and abundance into troubling decline.

The irony here is that the dead in our museums, which have through the centuries helped us to discover the diversity of life, continue to speak during an age of decline and extinction. By analyzing elements (stable isotopes) taken from specimen tissue, we can learn about the migrations of whales, birds and insects, for example, and know the diets and habitats of imperiled animals before we made a mess of their lives. The DNA still residing in these specimens allows us to construct trees of life (phylogenies) that reveal how all living things — viruses and orchids, whales and humans — came to be and how species relate to their closer relatives. Basically, from among the dead we can bring to light a story no less monumental and magisterial than the history of life on earth.

I myself have no particular research agenda, but I do have bigger aspirations for these 528 butterflies — and an ulterior motive. Before winter is over, I will drive them south in their boxes, along with dragonfly specimens I have, so that they can join two resplendent insect collections in Gainesville, Florida, where they can be of benefit to other scientists.

Working among millions of dead insects in these collections is my idea of a Florida vacation. There I can gawk at Goliath Birdwings of New Guinea, among the biggest butterflies on earth (as big as your hand) and glowing lemon-lime like little else in nature, or marvel at Scarlet Dwarfs from Japan, among the smallest dragonflies, no bigger than a paper clip (the small ones), but burning red and orange like an erupting volcano.

To dwell in museum collections is to follow the paths of Linnaeus, Darwin and innumerable other biologists before me — to see what they saw, study what they studied, learn as they learned. My journey to a collection in Copenhagen, for example, was a pilgrimage to the 1700s with the very specimens that famed entomologist Johan Christian Fabricius used to describe to the world insects I myself routinely see on the wing. To visit with his archetypal specimens (“type specimens,” as we call them) is like a constitutional scholar seeing an original copy of the Declaration of Independence or a baseball fan holding one of Babe Ruth’s bats.

Among the lifeless, I also experience wistfulness. While visiting insect and bird specimens at Yale University, I touched extinction: an Ivory-billed Woodpecker that almost certainly flies no more on earth, and magnificent Regal Fritillary butterflies (now gone from much of their former range in the eastern United States) that once fluttered not far from my own home here in Vermont.

I am not yet convinced that we humans, through our governments, have the capacity to solve the biodiversity crisis, to reverse or even slow the harm we’re causing to wildlife and wild places. In many ways, we’re losing biodiversity before we might even learn from our specimens about how to save it.

To be sure, there can be no substitute for a butterfly dancing across a summer wildflower meadow. But biological specimens, whether they reside in Copenhagen or are rescued from a thrift shop in New York, put on display for me the grand diversity of life on earth — and make extinction less an abstraction. In that way, if we are worthy, the dead may yet honor us. I’m just not sure we’re worthy.

A Sampling of the Cache of 528

(Not so flashy, but precious nonetheless.)

Postscripts

My gratitude for the gifting of these specimens goes to field naturalist Sean Beckett and to his father David, who rescued them from the gift shop for Sean.

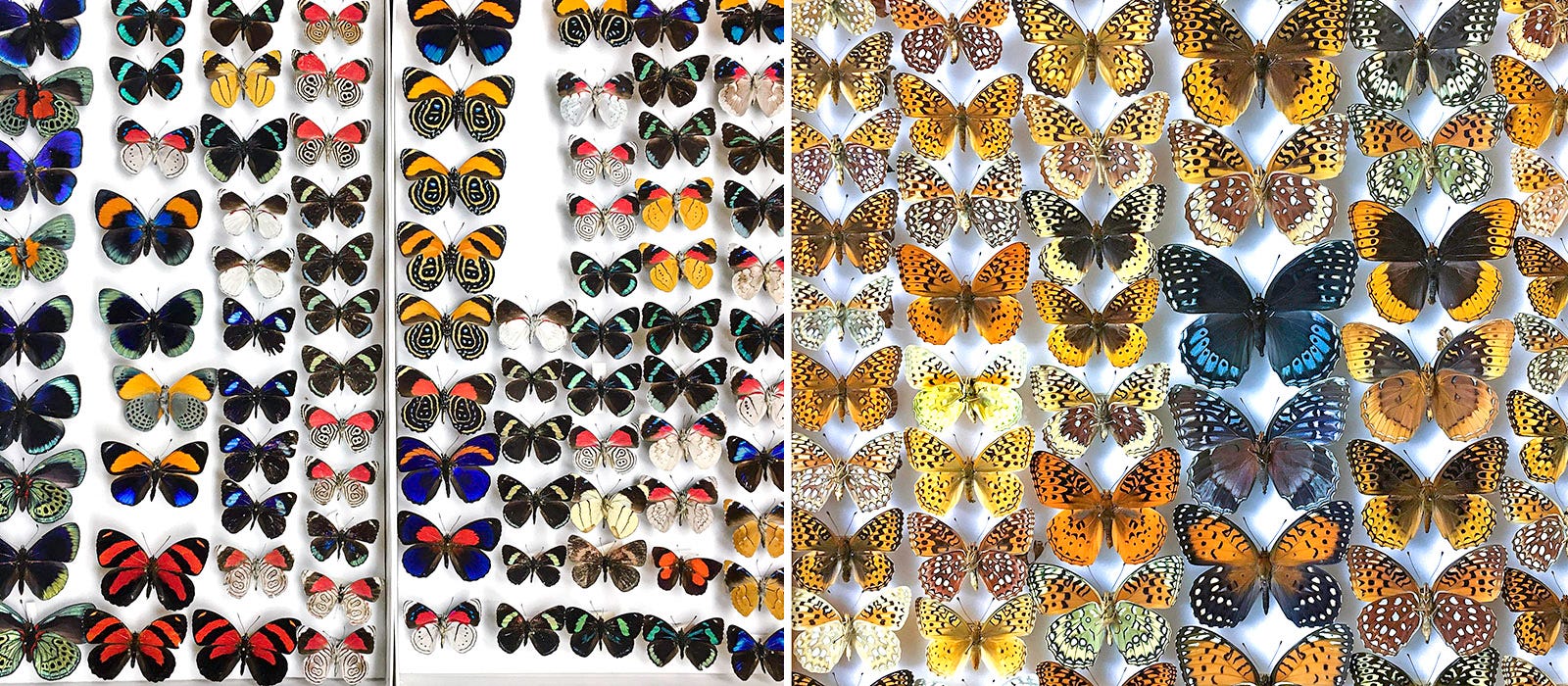

Butterflies in the top banner image reside at the famed McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity in Gainesville, Florida, where I am grateful to study among its 10 million butterfly and moth specimens. The two colorful sections on the left in that image are tropical butterflies in the family Nymphalidae; to the right are North American fritillaries in the genus Speyeria.

Also in Gainesville is one of the world great dragonfly collections, housed among another 10 million specimens at the Florida State Collection of Arthropods, where I am also grateful to study.

Thanks to Dave Wagner for his comments on an early draft of this essay.

Well this one is so beautiful and heart-wrenching it brought me to tears.

Many thanks, Bryan, for another wonderful piece. It immediately brought to mind my collections of childhood, poorly mounted and soon devoured by beetles, and also, importantly, the hours and hours I spent outside in the sunshine, chasing butterflies with a net, less concerned about catching them and more interested in just happily running around. That was a gift that continues to shape me.