Lincoln, Darwin and Nature

Born on the same day 215 years ago, the two men never met but almost certainly had wildlife in common.

ON FEBRUARY 12, 1809, in a log cabin in Hodgenville, Kentucky, a boy was born to impoverished parents who could neither read nor write. On the very same day, at the stately Mount House in Shrewsbury, England, another boy was born to parents of privilege and intellect.

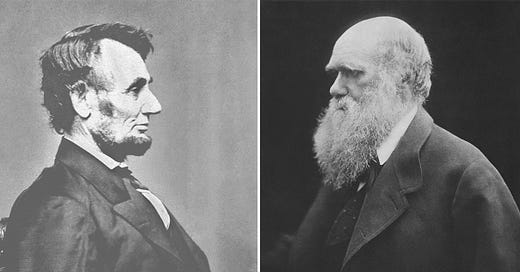

Abraham Lincoln would go on to become the U.S. president who won a war for the fate of his nation and unshackled its enslaved people. Charles Darwin would become the naturalist who won a war for a new idea and gave humanity the knowledge of how we came to exist.

Although Darwin and Lincoln never met, they were aware of one another’s aspirations. While historians, scholars, and journalists have explored the torment and accomplishments of these two men born on the same day, none seems to have written on how their lives might have intersected in nature, including plants and animals most of us encounter in our own lives of torment or accomplishment.

Both men knew hardship. Lincoln survived malaria, smallpox, and what was probably mercury poisoning. Darwin endured vomiting (including from seasickness), gut pain, headaches, and skin problems. Losing three children each, both suffered from depression.

Darwin was an abolitionist and Lincoln was likely receptive to ideas of evolution by means of natural selection. Having traveled extensively as a naturalist, Darwin of course experienced far more of the natural world. But each man, on their home continents, may have encountered a smattering of the same plant and animal species. The most likely was Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) (pictured in the banner image above).

Native to North America and Eurasia, Mallard has been and remains one of the world’s most widespread and identifiable birds. Even as boys playing or hunting outdoors, it’s a good bet that Darwin and Lincoln noticed Mallards dabbling in ponds or rivers. Mallards still dwell near the birthplaces of both men — they dabble near most of you as well.

Next on Darwin and Lincoln’s shared life list of birds might have been Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica), called simply Swallow in the U.K., one of the most widespread and charismatic land birds on the planet, and hard to overlook swirling and chirping over farm fields and other openings. Beyond swallows, well, my speculation becomes even more conjectural: Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), a force of nature wherever it flies, would have been unforgettable to either man; and although they are hard to find, Barn Owl (Tyto alba) is the most widely distributed owl in the world.

At least one common insect likely fluttered in and out of Lincoln and Darwin’s separate lives: the butterfly Vanessa atalanta, known as Red Admiral in North America and previously by the superior name Red Admirable in England. Flashing its red bars, this butterfly would have been obvious sipping nectar from cherry blossoms in Washington, D.C., or darting through the botanical gardens of England.

Because land plants weren’t as widely distributed two centuries ago (and because I’m only a wannabe botanist), I’m out on a limb (and playing the odds for a shared plant) with my choice of Common Bracken (Pteridium aquilinum), which is one of the most cosmopolitain vascular plants in the world. Darwin no doubt knew this robust fern. Lincoln perhaps did not, although it might have brushed his long legs as he walked woodland trails of the U.S. capital.

Finally, although mammals are perhaps tougher for me to predict, I’ll go with Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes), which is widespread on both continents and memorable whenever it is encountered — by a president, a biologist, or any of us.

Again, all this is pure speculation on my part. I have not consulted either man’s writings for this post. Other international species may be more likely, and I could be wrong about much of this (even though most of these species are hard to overlook). Besides, Lincoln, with bigger problems throughout his life, wasn’t known as someone who spent time close to nature.

Whatever the case, on their shared birthday I will pay my respects to the great emancipator and to the most pivotal biologist who ever lived. I’ll wander to the river below my home, where I can sit and reflect on how humans have destroyed so much of the natural world, and yet how much it ironically remains unchanged. All the while, there beside the river, perhaps as Darwin and Lincoln themselves would pass the time, I expect to be watching the Mallards that usually feed nearby along the banks.

Postscripts

As I’ve pointed out, this nexus of Darwin, Lincoln, nature, and us is purely speculative on my part, informed by my own life in nature and by my consultation with the online dataset (currently 2.67 billion records and growing every day) at the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). I’ve excluded species that were purposefully or accidentally introduced to new places (largely from Europe to North America), such as House Sparrow, Norway Rat, German Cockroach, and various grasses. My choices are also biased toward species readily recognizable and probably given at least some colloquial name two centuries ago (although many had only been first and formally named by Carl Linnaeus 51 years before Darwin and Lincoln were born).

I do wonder whether Common Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), after its introduction to the U.S. by European settlers, had already spread widely enough for Lincoln to have noticed it.

Although its cousin Painted Lady (Vanessa virginiensis) is more widespread in the world, the Red Admiral/Admirable was probably more constant and recognizable among very few worldly butterfly species.

Admittedly, some of the species I’ve chosen are of different subspecies in North America and Europe. But I don’t mind because the experiences of encountering them is no less wonderful.

Lincoln had an unwitting fraught relationship with plants. Although few knew of its toxicity at the time, the plant White Snakeroot (Eupatorium rugosum) killed his mother Nancy Hanks Lincoln at age 35, when Abe was nine years old. Cows ate the plant and passed on its toxin to many settlers as the terrible and lethal disease “milk sickness,” which may have killed other members of Lincoln’s family.

Portrait photos of Lincoln and Darwin are in the public domain and available thanks to Wikimedia Commons. The Drake Mallard image is © Bryan Pfeiffer.

CORRECTION: This post initially listed Great Egret (Ardea alba) and Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) as candidates. While both men might have encountered those two species during their lifetimes, largely owing to Darwin’s peregrinations, they were rare in the U.K. back in the day. (Many thanks to

for pointing this out.)

Lincoln did one very important thing for what would eventually become a part of “America’s Best Idea”.

President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Valley Grant Act, Senate Bill 203, on June 30, 1864. The legislation gave California the Yosemite Valley and the nearby Mariposa Big Tree Grove “upon the express conditions that the premises shall be held for public use, resort, and recreation.”

The Act represents the first time the federal government acted to protect and preserve scenic lands. Conservationists persuaded Senator John Conness of California to introduce a bill to keep Yosemite Valley from being ruined by increasing commerce and tourism.

Thanks, Bryan, for drawing out the living thread that connects these two. It would be nice to know of them conversing on the natural world, but stitching them together with Mallards and Red Admirables is lovely.