"Running Talus" Revisited

How a 50-year-old essay changed my life, and to this day offers us equanimity from a pile of rocks

Although this essay is more personal than usual here at Chasing Nature, I believe it has universal relevance (even for those of you who don’t run wild in mountains).

HALF A CENTURY AGO, as a 17-year-old boy, which is to say a fairly naive lump of flesh, I lived to touch rock and defy gravity. Before I knew much of anything about the world or gained any genuine sense of myself, I was a mountaineer.

At most every opportunity, my pals and I would flee the middle-class outskirts of Detroit for the Rocky Mountains, Yosemite, the Tetons, the High Sierra, the Cascades, and other lofty destinations across the continent, whereupon we would ascend to the high summits: Longs Peak, Half Dome, Grand Teton, Mount Rainier, Devils Tower, Mount Washington.

Other than adventure, I was aware of no ideology driving me ever higher, which was fine. I went up, enjoyed the views, and gained a sense of accomplishment. Even at altitude I held no philosophy of mind and body and mountain. That changed in 1975 when I read an essay titled “Running Talus.”

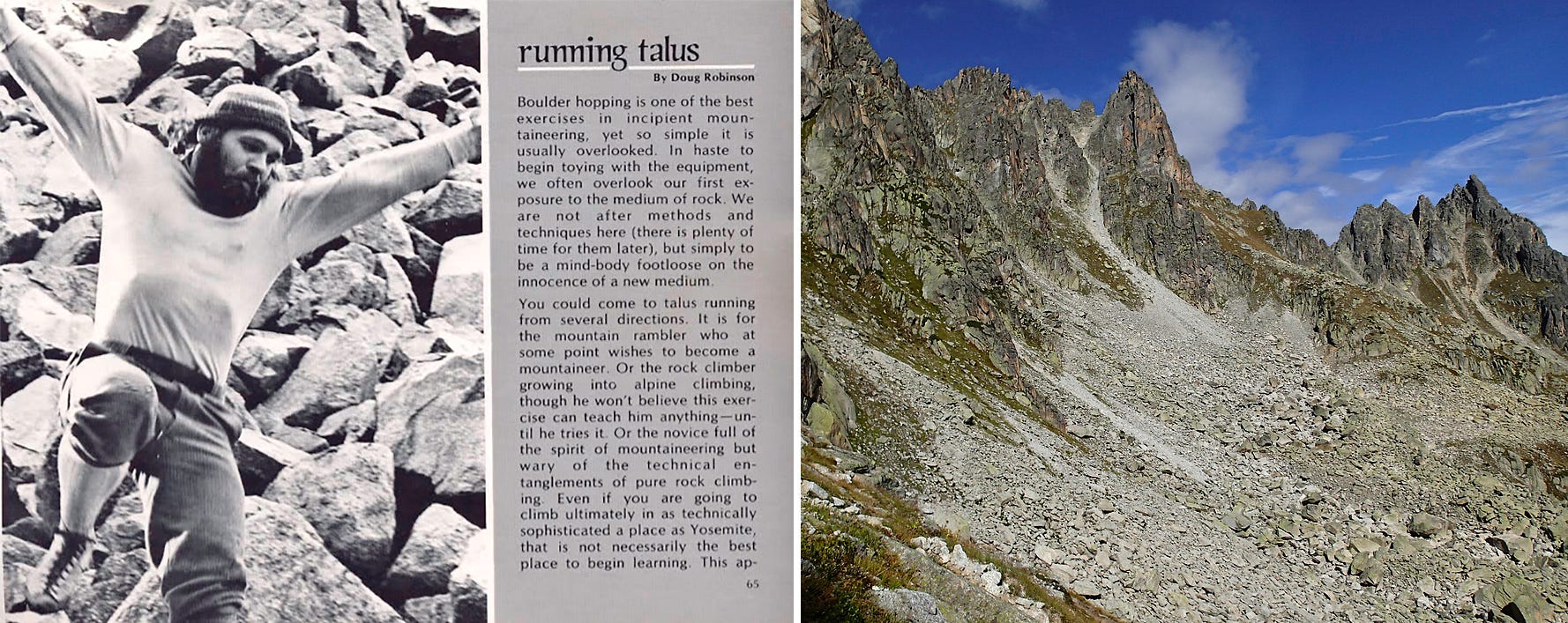

Written by an influential and counterculture rock climber, Doug Robinson, and published in the second Chouinard climbing equipment catalogue, the essay wasn’t specifically about climbing a rock face or a mountain — and yet was entirely about climbing a rock face or a mountain. Most important to me, however, and to the many climbers who read “Running Talus” at the time (and who no doubt remember it still), Robinson’s seminal essay kindled in me a profound sense of mountain and mindfulness.

Although I had come close to experiencing something like it as an exuberant boy on my red, one-speed Schwinn Typhoon, the actual act of running talus, which Doug and I will explain to you soon enough, was my discovery that mind, body, and earth could weave and flow and exist as one. By no means novel, this kind of synthesis is perhaps more relevant now as so many of us look to escape artifice in the culture for equanimity in nature.

“Running Talus,” which turns 50 this year, has aged far better than my knees. I bring you perspective on the essay only days before I submit to the replacement of my left knee. (I got a new right knee in 2022.) My era of running talus has long since passed, even before my knees went bad. No matter. My insights on the talus slopes a half century ago guide me to this day. And for any of us, running talus, or any transformative experience in nature, is as foundational to our existence and well-being as bedrock and breathing.

What is Talus and Why on Earth Run Across It?

At its most basic, talus is a field of rocks situated on the lower flanks of a mountain or at the base of a cliff. A talus slope can be many acres in breadth, and its rocks and boulders and slabs, for running purposes, generally range in size and shape from footballs to trash cans to pianos. For the most part, talus slopes are stable, but their individual rocks can pivot or shift or give way entirely under foot. Apart from quicksand or a minefield or a tightrope, talus slopes are among the worst places to go for a run. And among the best.

To a climber, a talus slope is often an inconvenience — something to get past on the way to or from either the base of a cliff or the more solid rock of a mountainside. But Robinson saw talus as opportunity — a place where novice climbers could begin to gain intimacy with rock (and discover so much more). Rather than rope or climbing hardware, all anyone needs to run talus is at minimum an old pair of sneakers, a body, an open mind, and movement. “People don't teach you to climb,” Robinson wrote, “the rock teaches you.”

To run talus is to embrace risk and to know the power of yourself. It is running on the edge, a blend of balance and momentum and glancing just ahead at what’s coming next. Every foot-fall is a micro-second deliberation and an act of unmitigated instinct. The best talus running is downhill: the runner benefits from gravity, uses it, flows with it, rather than allowing gravity to exert its force upon the runner. In that sense, a talus runner is gravity embodied.

“Moving over the talus, we begin to see that coordinating the step from one point of balance to the next implies another quality — rhythm,” Robinson wrote. “A good dancer becomes a good climber; the mere weight lifter is helpless. We build up momentum. Each step becomes less of a stance, more of a brief way-station to the next step. The dynamic overcomes the static.”

A tentative talus runner who overthinks things may tumble into a heap or, more to the point, squander the purpose of running talus. Nope, sorry, the purpose is not to find some sort of nirvana. It is instead an affirmation of body and mind navigating and caressing the contours and complexities of Earth. It’s a lot like life. We do it every day, some days better than others.

In one sense running talus is a pure manifestation of prowess (especially on youthful knees). It is therefore a kind of self-affirmation derived of rock and gravity, flesh and bones, neurons and purpose — an affirmation far more genuine than “likes” and “followers” and other forms of self-esteem sought and expressed online. And when it’s going well, running talus is far more, something greater than the sum of what’s happening, something beyond self, and evocative of what’s available to any of us anywhere in nature: transcendence. “The secret is to relax and let yourself learn without thinking of what you're doing,” Robinson wrote.

Transcendence, of course, is well-worn terrain in nature writing. Nonetheless, at least for me at age 17, running talus was epiphany. Before reading the essay, I had experienced only hints of the sublime while descending talus. “Running Talus” released me to take risk, to experiment, to discover more about how to live. I don’t recall ever falling while running talus, or at least getting hurt. I only recall, vividly, even now, especially now, the exhilaration and wholeness of mind, body, motion, gravity, rock.

A half century later, with those talus runs far behind me, where might I now find my prowess? How do any of us adapt gracefully as the body begins to decline? For me, well, no mystery: it is walking in nature. Running talus becomes walking earth — a philosophy. I express it regularly in essays published here at Chasing Nature. Although I’m not always so explicit, every orchid or butterfly, every leaf falling or sun rising, every idea or revelation, no matter how prosaic, offers transcendence.

And so to wrap up I bring you not into the woods or to the rock, but to State and Main, the central intersection in my home city of Montpelier, Vermont. On each corner a lamp post is equipped with a button for a pedestrian to press in order to stop traffic and secure the right to cross. Upon pressing the button, but before gaining the “walk” light, we’re instructed by a disembodied electronic voice: “Wait!” In my decades of pressing the buttons at State and Main, I’ve noticed that about half of the walkers do not wait — they cross against the light.

I always wait.

I stand on the corner and take in the beauty, idiosyncrasies, and surprises of my city and its inhabitants. From that intersection, I’ve seen a Bald Eagle soaring overhead and Peregrine Falcons hunting downtown pigeons. I’ve watched Canadian Tiger Swallowtail butterflies floating high over the Capital City and Monarchs weaving in and out of traffic. And most every August at the intersection, I witness the arrival, from parts unknown, of Wandering Gliders — golden dragonflies that swarm into the downtown, some of them flying but a meter or two from folks crossing the street against the light.

State and Main is a long way from any talus slope. Or is it? Fifty years ago I began to run talus and learn more about the wonder of being alive. Since then I’ve worn out two knees chasing nature in all its beauty, complexity — and fragility. Apart from death, nothing is guaranteed (not even getting through a knee replacement).

So as any of us might confront fear, injustice, the arrogance of power, or our own personal challenges, we find strength and equanimity in one another, in nature, and within ourselves — whether we move like the wind over talus, wander the trails for songbirds, or even pause to watch the world go by while waiting to cross the street.

I’ll meet you out there soon on a new knee.

Postscripts

On his way to climbing consciousness, Doug Robinson, who turns 80 this year, was a distance runner, a resident of the Haight-Ashbury, and a pioneer in eco-friendly climbing. He’s been described as “John Muir meets Jack Kerouac.” Here’s “Running Talus,” first published in the 1975 Chouinard Equipment catalogue. Yvon Chouinard’s gear design and manufacturing company went on to become Patagonia, Inc.

As a corollary to this essay, my friend

, a poet of insight, has included a kind tribute to me in his essay titled Science and the Sacred. Discover Scudder’s poetry and prose here on Substack at .

I could feel your feet as they grazed the stones, the magical balance and finesse. A great piece for our times. Good luck with the knee!

My talus slopes are on the Winooski River when in my kayak I face a rocky stretch of very light whitewater (No heavy rapids for this 80 year old) and feel one with the river and my body as I paddle and hip-wiggle my way through the channels and froth——whee! Thank you for the challenge to think about things. Best of luck with the new knee. The body has an amazing ability to heal.