The Little Butterflies You’re Overlooking

Grace Among Grass Skippers (and a Zombie Snail Update)

THEY DISPLAY neither the elegance of swallowtails, the sparkle of fritillaries, nor the fame of the Monarch. To be honest about it, as butterflies go, they’re somewhat chubby, inornate, and elusive.

And yet among the skippers — butterflies now on the wing at your feet — you will find diversity, joy, and meaning. To wit, I bring you Mulberry Wing (Poanes massasoit), a skipper serving as a reminder that even the ordinary in nature can invoke in us feelings of joy, sympathy, and kindness — more of which the world could use right now.

But before you can fully appreciate Mulberry Wings, you need to know a little more about skippers. They’re different. For one thing, skippers have stocky bodies, especially the thorax, where the flight muscles reside and where the four wings are attached. As a result, skippers tend to dart rather than flutter and float like most butterflies. Perched for you in an instant, skippers are gone the next. In flight they move like olympic triple jumpers or kids skipping erratically through a wildflower meadow.

It doesn’t help their cause any that skippers present some of butterfly watching’s greatest identification challenges. They’re the sparrows of butterflies. (This is particularly true for one subgroup of skippers called the duskywings in the genus Erynnis. Basically, if skippers are the sparrows of butterflies, then duskywings are the sparrows of skippers.) But all you need to know at this point is that your introduction to skippers can begin with the most common among them — there in your backyard, the flower garden, the meadow, or marsh: the grass skippers.

Tiny and often orange or yellow, grass skippers pose and dart like candle flames flickering across the landscape. And they’re all around us (kind of like grass). My home state of Vermont, for example, by no means a bastion of butterfly biodiversity, has two dozen grass skipper species, none of them much bigger than a postage stamp and all of them best identified by distinctive patterns and colors on the underside of their hind wings, which they reveal to us upon landing and folding those wings closed above their bodies.

But only if they strike that pose long enough for us to look, rather than darting away from novice observers who might otherwise pass them off as little moths. (Well, uh, as it turns out, butterflies are actually specialized day-flying moths, but that’s a different story for another dispatch — and a postscript below.)

Which brings us to the Mulberry Wing (in my banner image atop this post), whose underwing pattern resembles a yellow airplane and who is among my most favorite of insects. Yeah, a grass skipper rates that highly in my personal tree of life.

To behold a Mulberry Wing you must usually get your feet wet. Mulberry Wings tend to live in seepy, sedgy meadows and marshes, where the females lay eggs on Tussock (Carex stricta) and perhaps other sedges. While you’re there in the wetland, various other skippers might dash to and fro, fast and blurry. But not necessarily the Mulberry Wings.

Mulberry Wings instead float among the sedges, sometimes flapping hard and fast without getting very far for their efforts. They’re a bit like fledgling songbirds — clumsy and wayward on the wing and oblivious to the likes of you standing there watching … and usually smiling. Mulberry Wings are like 10-year-old kids playing ice hockey: cute in their awkward determination. As they waft among the sedges, I often find myself cheering on the Mulberry Wings toward whatever their appointed destinations. In flight they are endearing. And I mean endearing in its literal translation: inspiring affection or love.

Four years ago this week, while on assignment photographing butterflies for the state of Maine (a very good gig), I found myself in the good company of Mulberry Wings going about their business in a wetland that happened to have a lone Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) plant in bloom. Swamp Milkweed nectar is butterfly candy.

My fate was set. I pushed away vegetation to create an opening in the wetland, parked myself a few feet from the milkweed, and waited for the Mulberry Wings to visit. (This is why I sometimes wear camouflage clothing while chasing insects and birds.) For nearly two hours, I knelt or sat in the wetland …. simply waiting. Nothing more.

A myriad of insects came in for nectar, including a Hummingbird Clearwing moth (Hemaris thysbe), a Great Spangled Fritillary (Speyeria cybele), a Silver-spotted Skipper (Epargyrus clarus), and several Black Dash skippers (Euphyes conspicua) — each a reward for my patience (although I neither demanded nor warranted any of it). And, yes, all the while, now and then, the Mulberry Wings would come and go as well, flashing their little yellow airplanes at me, almost as if they knew of my aspirations.

Although I try not to play favorites in nature (and usually don’t succeed at it), I am unabashedly partial to Mulberry Wings. I don’t suppose a Mulberry Wing will ever break my heart (except for the usual heartbreak of the human assault on nature). So, had they not come to the milkweed, I would’ve been fine. After all, I’d spent two hours sitting beside a single plant waiting for a little butterfly. No email. No phone. No politics. No wars. The realities and pains of the world would inevitably return soon enough. But there in the wetland, I held my sacred ground, my vigil, my respite.

How often do any of us sit in one place in nature and devote two hours to nothing more than watching what comes and goes? Not enough, I suspect. Each time I manage to pull it off, it is among the best two hours of my life.

Postscripts (Including the Zombie Snail Update)

For another sense of scale, below is a pair of Long Dash skippers (Polites mystic) making more Long Dash skippers.

To witness the breadth of grass skipper diversity, here are more than 1,200 species around the world, displayed in decreasing order of abundance, thanks to the amazing iNaturalist. And here are Mulberry Wing records from their range across the American Midwest and Northeast (barely reaching into Ontario and Quebec).

In my skipper montage above, clockwise: Common Branded Skipper (Hesperia comma), Peck’s Skipper (Polites coras), Fiery Skipper (Hylephila phyleus), Delaware Skipper (Anatrytone logan), Southern Broken Dash (Polites otho), Essex/European Skipper (Themelicus lineola).

As many of you know, for more than a week now I’ve been spending hour upon hour with parasitic flatworms that live in bird guts but spend a portion of their lifecycle inside common amber snails (Succineidae), making the snail’s eye stems pulse and flash like bizarre caterpillars. I’m in deep (figuratively) with these parasites, reading the scientific literature, observing behaviors, and getting some lovely photos and video. For now, however, I’m off for about 10 days in the wild, after which I’ll have a full report on the “zombie snails” for you. Until then, here’s a short GIF snippet. (If it’s not automatically animated, try clicking the image.) And in case you were wondering, uh, those aren’t your normal amber snail eyes and eye stems.

Bonus Butterfly Taxonomy

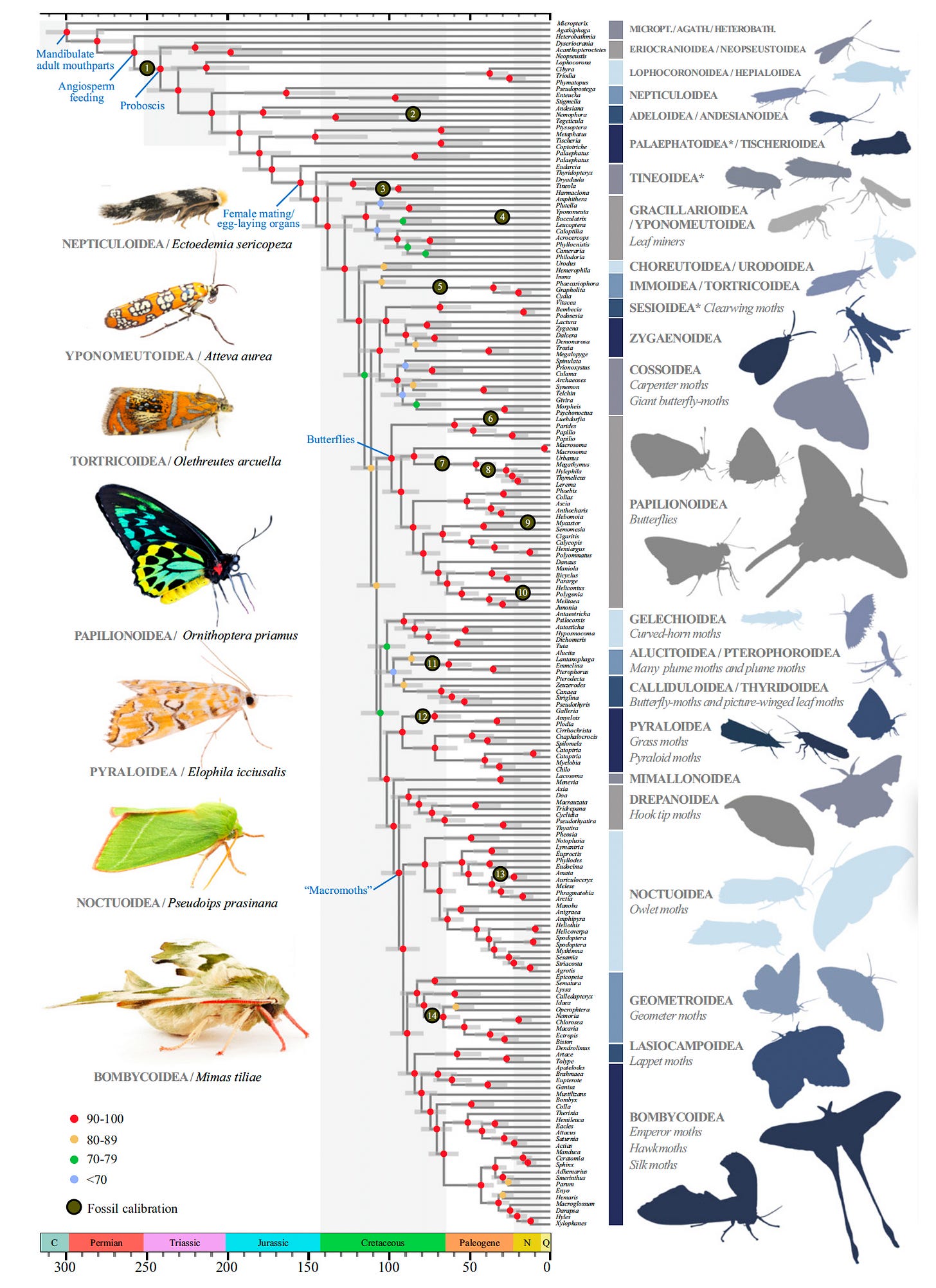

For quite some time, we butterfly people didn’t quite know what to do with the skippers. Are they indeed legitimate butterflies? Or something else? And where do they belong in the taxonomy of the insect order Lepidoptera (the moths and butterflies)?

Butterflies themselves constitute a separate superfamily called the Papilionoidea — the “true butterflies.” The skippers, for a while, weren’t among them, instead assigned their own superfamily, Hesperioidea. As a result, skippers were in some ways taxonomically more moth than butterfly.

Over time, however, with the potent tools of genomic sequencing, lepidopterists have been revising the moth and butterfly tree of life. We’ve worked out our issues with skippers, and now bestow upon them a rightful place (in the family Hesperiidae) among the true butterflies. So, yeah, skippers are indeed butterflies.

But as I pointed out, the butterflies, the Papilionoidea, are merely a superfamily among many other moth superfamilies (all together in the Lepidoptera). Butterflies, including the skippers, are basically a kind of day-flying moth that diverged from other moth lineages around 100 million years ago.

Among 180,000 or so known Lepidoptera species in the world, roughly 90 percent of them are moths. The butterflies are a distinct minority among the Lepidoptera, and in some ways merely another superfamily among many moth superfamilies. So, yeah, in that sense, butterflies are moths. Here’s one way to look at it, starting from some proto-moth 300 million years ago (upper left). What we now call butterflies (Papilionoidea) are in there among lots and lots of moth superfamilies.

Reference for this phylogeny: Kawahara, Akito Y. et al. Phylogenomics reveals the evolutionary timing and pattern of butterflies and moths. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Vol. 116, No. 45. October 21, 2019. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1907847116

Whether it is for two hours or twenty minutes, I find sitting in one place in nature with the singular purpose of watching what comes and goes to be cathartic.

So many incredible insights, thank you! I love picturing Mulberry Wings as “10-year-old kids playing ice hockey: cute in their awkward determination.” 🥰🦋