Virtue in a Little Brown Butterfly

After 21 years of searching, I’ve discovered one of the most elusive butterflies on the continent in my home state of Vermont. Will anyone care?

ALMOST EVERY SPRING for the past two decades, I would on various days grab my insect net, get myself to the woods, and bushwhack to spruce bogs across Vermont. Along the way on these walks I would encounter lovely nesting songbirds, clouds of biting insects, lady’s-slipper orchids, and the challenges of my growing old as a field biologist.

No matter how long or arduous the walk, how bruised or bitten my body, or how many times I’d mutter to myself, “I’m getting too old for this shit,” the moment I would arrive at the bog was the moment everything in the world went right.

A spruce bog is an open, squishy mat of sphagnum moss that soothes tired bare feet. It is hot pink rhododendrons in bloom and fat cranberries leftover from last autumn. At bogs I find rare birds, audacious dragonflies, and some of the first butterflies of spring. More to the point, upon arriving at each bog over the course of those two decades, I would immediately get to work searching for one butterfly in particular, a fantasy called Bog Elfin.

No bigger than a penny and patterned in black, browns and rust, Bog Elfin (Callophrys lanoraieensis) is one of the smallest and most elusive butterflies on the continent. Not only does it spend most of its life high in the boughs of black spruce trees, Bog Elfin is on the wing and detectable for only a few weeks from mid May to early June. “If you are willing to travel to remote black spruce bogs and feed ravenous mosquitoes and black flies,” one lepidopterist of note has written, “you’ll have a chance of missing this mysterious butterfly yet again.”

So it was no wonder that despite Vermont’s abundance of bogs nobody had ever seen a Bog Elfin in the state. And for 21 years, year after year, bog after bog, I myself maintained an unbroken record of missing this mysterious butterfly yet again. Until this year — when I discovered a Bog Elfin flying at a spruce bog in northern Vermont on May 19.

It fluttered from a lofty perch to alight on a waist-high spruce about 20 feet away from me. When alone in bogs, I’m not inclined to talk to butterflies. But after raising my binoculars for a positive identification, I spoke to the elfin. “I’ve been looking for you,” I said, “for a very long time.” At which point the Bog Elfin launched and zoomed up and away before I could snap the photo necessary to convince the world (or at least my friends and colleagues) of my discovery.

So as I searched for the escapee or for another elfin, I began to ponder the significance of my discovery. Sure, I felt elation and vindication. I had often joked that I would discover this butterfly in Vermont or die trying. At the bog I had notions of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea and his champion marlin lost to sharks as he hauled it in to shore. I remembered Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury character Richard Davenport, a birdwatcher who at long last tracked down a rare (now extinct) Bachman’s Warbler only to die of a heart attack during the encounter.

Then I had a crisis of meaning at the bog. After all, what good is a butterfly that virtually no one will ever see? Why in the world would anyone else care about the Bog Elfin?

Age and Experience

Since my discovery (and since I didn’t die in the bog), I’ve come up with three reasons why anyone would give a damn about a little brown butterfly. The first occurred to me while continuing my search at the bog: experience.

It takes skill to find a Bog Elfin, to recognize its habitat, to sense where it might perch or seek nectar, to know how it carries itself and how its aeronautics differ from those of other little brown butterflies and moths flying around the bog. That awareness took me years to fully realize. And I suspect my failures during the first decade or so of searching for Bog Elfins were in part due to ignorance and “user error” — looking in the wrong places and at the wrong time.

Maybe a younger person with sharper eyes and quicker reflexes could have found this butterfly before me, which would have been fine (and yet deflating). But I like to think that the patience, grounding, and skill that come with being a 65-year-old field biologist still count for something, that slowing down in almost every way still counts for something (which for many of us might be a holdover from our time living without the internet). I now navigate bogs at a more contemplative pace than I did 20 years ago. As an entomologist, I swing a net in the prime of my career, even as professional athletes half my age enter the twilight of theirs. Musicians and artists gain dexterity and artistry with age, while athletes retreat to jobs on television or as product pitchmen.

So sometimes, at least in pursuit of a little brown butterfly, the journey actually is the story. So is longevity and knowledge, which I like to think continue to be of some use in the world.

Conservation and Morality

Let’s be honest: Bog Elfin is hardly charismatic. It has no legion of besotted fans, no “Save the Bog Elfin” campaigns. There’s no money in Bog Elfins, no influencers, no social media presence at all. So by those measures, Bog Elfins aren’t worth much to anyone. We’re not talking pandas or polar bears here.

Although little brown butterflies make my own heart pound, I recognize that it would be easier to make a public case for the Bog Elfin if it were big and glittery and purple — or at least endearing like an Orca or an orchid. No luck there. So let’s go instead with morality.

This butterfly is vulnerable or imperiled across most of its known range, which historically had been bogs in very few scattered locations in northern New York, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine; and similarly across Canadian provinces from Ontario to Nova Scotia. Our threats to those bogs and their elfins include global warming, commercial harvesting of peat moss, draining for commercial development or flooding as a consequence of it, and insecticide spraying for spruce budworm or mosquito control. Now that I’ve discovered Bog Elfin living here, we Vermonters join the handful of states and provinces entrusted with protecting this butterfly from decline or extinction. It shouldn’t be too difficult: my discovery came on protected, state-owned land.

Still, I hear voices, naysayers: Do we really owe anything to the Bog Elfin? It doesn’t tweet or turn a profit or pose with us for selfies. What’s it done for us lately?

One idea in defense of nature, which comes from environmentalists in academia, think tanks, and other high-minded places, is to show that there’s money to be made or saved in protecting biological diversity. Ecosystems like bogs provide us with tangible “services” to which we can assign dollar values: mangrove swamps and barrier islands protecting us from coastal floods or storm surges, for example, or forests sequestering carbon and easing the climate disaster. All of that may be true, and yet it doesn't seem to be persuading enough people in power to put those principles into practice.

So, to look at it another way, here in the United States we protect speech we don’t necessarily care for, or that might lack obvious intrinsic value. It is a foundational doctrine — it makes us stronger, more open to ideas. The same is true for wildlife and wild places. Protecting them makes us stronger. It professes that we might actually step off our destructive path and live more aware of nature, more responsibly with nature, in reverence of nature.

Most of us will never see a Polar Bear, but we know that the Arctic is a better place for having them. Without the Eiffel Tower, Paris would still be a great city, but it wouldn’t be the same Paris. A bog without Bog Elfins is still a bog. Its orchids still glow like little purple flames across their mossy carpet; its sparrows and warblers still sing with verve and vitality. But a bog is more so a bog with its little brown butterflies. They’ve flown in these places long before we arrived on the scene to make a mess of things. And we ourselves are more human when elfins remain on the wing in their bogs.

In our safeguarding little brown butterflies, like protecting speech, we show reverence not only for the popular and charismatic and profitable, but for the obscure and the vulnerable as well. Vermont is now a better place for having Bog Elfins — up there in the spruce where they belong, overseeing the orchids and songbirds and blackflies, even aging biologists like me. Protecting little brown butterflies is good for the integrity of nature — as it is for integrity of humans.

Little Brown Butterflies and You

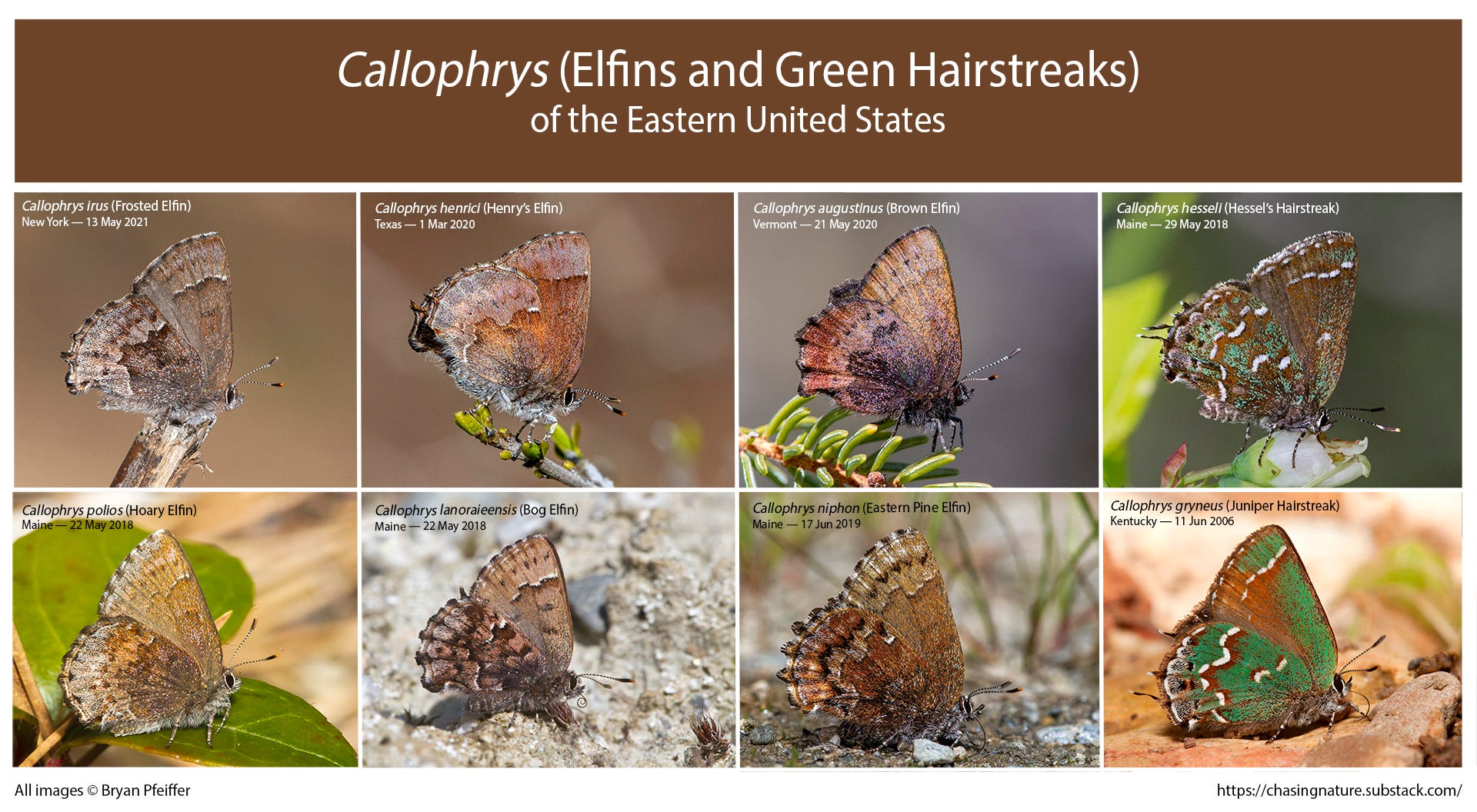

Finally, if all of this fuss over a butterfly might still come across as an abstraction, perhaps I can ground it for you closer to home. As it turns out, the Bog Elfin has many close relatives — at least 80 similar species worldwide (including little green butterflies called hairstreaks) in the genus Callophrys (which translates roughly to “beautiful eyebrow,” perhaps owing to the crescent-shaped markings on many of them).

To my mind, the elfins and green hairstreaks might be perfect butterflies. I say that not only because they inhabit all sorts of wild places — from arctic bogs to southern deserts, from cities to farms. And not necessarily because some of them have odd and specialized diets. But among their most endearing qualities is that Callophrys butterflies are exhibitionists: once you find one perched (my Bog Elfin notwithstanding) it will often pose for you in plain sight so that you might sit and watch it sipping nectar, laying eggs, or just being — for as long as you care to remain by its side. That included a more cooperative Bog Elfin posing, at long last, for my photo.

And once you gain that kind of intimacy with an animal whose lineage goes back 100 million years, perhaps then you will realize that a butterfly the size of your thumbnail is not only a gossamer insect, but an expression of time and place. A Bog Elfin lives only in the vicinity of spruce bogs — and nowhere else in the world. A Hessel’s Hairstreak can be found only in the company of Atlantic white cedar — and nowhere else in the world. Green Hairstreaks are now on the wing in Russia and in Ukraine. And wherever these butterflies live, most people have no clue that they exist.

I have dwelled with various species of Callophrys butterflies from deserts of California to the oil refineries of Texas, from the cave country of Kentucky to remote forests in northern Maine. I offer you a sense of their subtle diversity in the montage below (also showing how they perch with wings folded above their bodies, revealing their intricate underside markings).

Most of you reading this essay live not far from one of these little butterflies. Here in the U.S., for example, that would include either Eastern Pine Elfin or Western Pine Elfin, both of which resemble Bog Elfin. Both are on the wing now, and you need not bushwhack or endure blackflies to find one. Walk instead among the pines, stopping now and then to investigate the daisies, dandelions, asters and other common flowers, or even the dirt roads and trails where pine elfins often like to land.

Search for mottled triangles the size of pennies. Only then you might discover an elfin of your own. It won’t be a Bog Elfin, and it won’t take you 20 years to find. But if you’ve got the temerity to look, the exuberance of youth, or the wisdom of maturity, it will be your elfin, your discovery. It will be a manifestation of time and place. And it will perhaps offer you virtue in a way you had never expected from something as prosaic as a little brown butterfly.

"And once you gain that kind of intimacy with an animal whose linage goes back 100 million years, perhaps then you will realize that a butterfly the size of your thumbnail is not only a gossamer insect, but an expression of time and place." That line brought a thrill to my heart. With all the arguments for or against protecting various species, more and more I fall with the feeling that we don't need persuasion to know that we're all part of life together with these creatures, all relatives.

Beautiful. In all my years of conservation advocacy, I've never heard the argument that protecting uncharismatic or unprofitable biodiversity was analogous to protecting free speech, supposedly a bedrock of American greatness. That is one powerful argument, and I can't wait to use it the next time I find myself needing to defend those in the Web of Life who need defense!