SHRINKING VIOLETS

Flower Sex, Pollinators, and the Fate of Beauty

THE MOST ENDURING and beautiful relationship in the history of the world is the bond between insects and flowers. In their flirtations and commingling, the insects get nectar and the flowers have sex.

For at least a hundred million years this dance of evolution has produced ravishing color and alluring patterns. For those of us who care to look, flowers and insects are nature’s most approachable and magnificent displays of beauty, biological diversity, even story.

And yet even as we enjoy this matrimony, even as pollination gives us everything from apples to zucchini, fascinating new research suggests how easily humans, as we warm the planet and assault its insects, can upset this ancient relationship. It’s not as tragic as Romeo and Juliet or Orpheus and Eurydice, at least not yet, but it is concerning nonetheless.

In a catchy but inaccurate headline, The New York Times last week described the research this way: “Flowers Are Evolving to Have Less Sex.” Before I rectify that notion for you, I’ll summarize the study’s findings, published in the journal New Phytologist (Acoca-Pidolle 2023). The science here is a reminder that we humans possess both an aptitude for destruction of nature and the capacity to wonder and fret about its beauty and fate.

Pansy Sex Both Ways

Carried out near Paris, France, the research features the mating habits of a widespread plant called European Field Pansy (Viola arvensis), which is also an introduced species in the United States. Were it not so lovely and diminutive, most of you would probably call this pansy a roadside or garden weed. Many do. Regardless, pansies and related plants (they’re actually violets) normally have two means of reproduction:

They can sit there, look pretty, and wait for an insect to visit for nectar. As it moves around and sips its reward, the insect gets dusted with pollen, which it unwittingly carries and leaves on other flowers during its pub crawl. Called “outcrossing,” this distribution of pollen from flower to flower spreads genetic diversity, resulting in plants that are more fit for adversity in the struggle for existence. Lots of plants reproduce this way.

But the Field Pansy also can dispense with insects altogether and have sex by itself. Possessing both pistils and stamens, which is common among plants, a given flower can fertilize its own eggs with its own pollen. It’s called “selfing.”

A Resurrection

With insects declining at a troubling pace (Wagner 2021), the research team set out to determine whether pansies responded accordingly by more frequently selfing — and whether the flowers themselves had changed their structure or allure over time. And this is where the researchers — based at Université de Montpellier and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) — got clever and resourceful.

Because they had not been studying pansies over time, the botanists couldn’t exactly compare today’s Field Pansy flowers to those in bloom decades ago when pollinators, especially bees, were more abundant. Or could they?

As it turns out, the team had access to Field Pansy seeds collected from the Paris region from 1992 to 2001. By germinating those banked seeds and raising a population of pansies, the scientists could compare the ancestral flowers to their contemporary descendants. It’s a branch of study called “resurrection ecology.” Basically, the botanists could observe modern-day pansies living beside their very own ancestors. When they did, it turned out that the floral and reproductive changes were significant.

Rather than reporting that flowers were “evolving to have less sex,” the researchers discovered that they were having more sex — with themselves. Modern-day pansy flowers had increased their selfing rate by an average of 27 percent compared to their ancestors. Basically, with no bees involved in the pansy procreation, the flowers had evolved to reproduce more often without pollinators. But there’s more.

Today’s Field Pansy flowers in the study got 10 percent smaller and produced 20 percent less nectar than their ancestors. The flowers also displayed fewer nectar guides, which are sort of like runways on the petals directing pollinators toward nectar. (You can seem the on flowers pictured in this post.)

The researchers believe this floral evolution, which happened over the course of only 20 to 30 years, is a direct result of fewer wild pollinators in the study region. After all, nectar production, costly to a plant’s resources, is something a flower does only to reward insect visits. So why bother if the insects aren’t around and the flower can have sex with itself anyway?

In addition to documenting the flowers’ rapid evolutionary response to pollinator decline, the researchers identified a threat to a relationship that’s at least 100 million years old. In killing off insects, we humans may be setting in motion a cascade of ill effects, a kind of eco-feedback spiral that goes like this: The decline in pollinators causes a collateral decrease in nectar production among flowers, which in turn only exacerbates the pollinators’ problems because many insects rely on nectar for survival. Basically, the insects are victimized twice: first by humans and then by corresponding plant evolution. Called “selfing syndrome,” and not yet known to be a huge problem, it nonetheless warrants attention.

Another cool thing about this study is that the researchers recruited bumblebees in a kind of preference test pitting the contemporary pansies against their ancestors. When hives of Buff-tailed Bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) were placed among both pansy populations in the study, the bees more frequently visited the ancestral flowers, suggesting that they preferred larger, more attractive blooms with more nectar.

The Diminution of Beauty

Which brings me to notions of grandeur and grace (my own thoughts, and not conclusions published in the research). In their recruitment of flying insects for reproduction, plants over time have evolved some of the most beautiful ornamentation on Earth: flowers. It happened long before humans came along to pick bouquets, write sonnets, and plant gardens — all the while becoming a destructive force of nature against nature.

It’s bad enough that we’re killing insects. But it’s also sad to me that in so doing we’re making a few flowers a little less beautiful. After all, we need beauty in the world more than ever.

Then again, evolution, random at its core, doesn’t really give a damn about us and our floral affections. Accordingly, as it turns out, other recent research, on morning glories, suggests that in response to declining insect abundance flowers can evolve in the opposite way — to compete for scarce pollinators by getting bigger and showier and more outgoing in their outcrossing (Bishop 2023).

So perhaps both will happen. With 300,000 or so flowering plants in the world, we generalize about them at our peril. And sex, of course, is complicated. Discovering what happens next in the saga of flowers and insects and extinction will no doubt require ongoing research.

And yet here’s another idea: How about if we protect beauty and diversity by ending our slaughter of insects in the first place?

Postscripts

Because pansies are indeed violets (in the genus Viola), the evolution toward smaller flowers and more reserved sexuality means that my use of “Shrinking Violet” in the headline is both literal and figurative.

Speaking of headlines, the brilliant Carl Zimmer covered this research beautifully for The New York Times, and almost certainly did not write the headline above his piece.

In the case of pansies and other violets, the particular shape of the flower fosters cross-pollination — a situation that botanists call chasmogamy, which basically means “open marriage.” Violets in particular also produce flowers with shapes that foster selfing — what botanists call cleistogamy, or “closed marriage.” Field Pansy (the subject of this experiment), however, has only open-marriage (chasmogamous) flowers (Ballard 2023). It made the research more straightforward (at least I suspect so).

“The collapse of insects” by a team of journalists at Reuters is an informative and artistic account of the human assault on insect diversity and abundance.

Thanks to “manuscript” reviewers for this post, Josh Lincoln and Steven Daniel, and to my pal Rick Prum, “pale, male, and Yale,” as he puts it, who nonetheless has us all thinking about the evolution of beauty.

I had promised you some Chasing Nature housekeeping this week, including updates to our GO WILD portal for paying subscribers. But this pansy paper, which first came to my attention back in December, has occupied my mind ever since. (Many thanks to anthropologist and author Heather Remoff, who writes on sexual selection, for alerting me to the research.) I’ll get to housekeeping, including Snowy Owls, next week (unless I’m distracted by something outside or newly published).

Gratitude

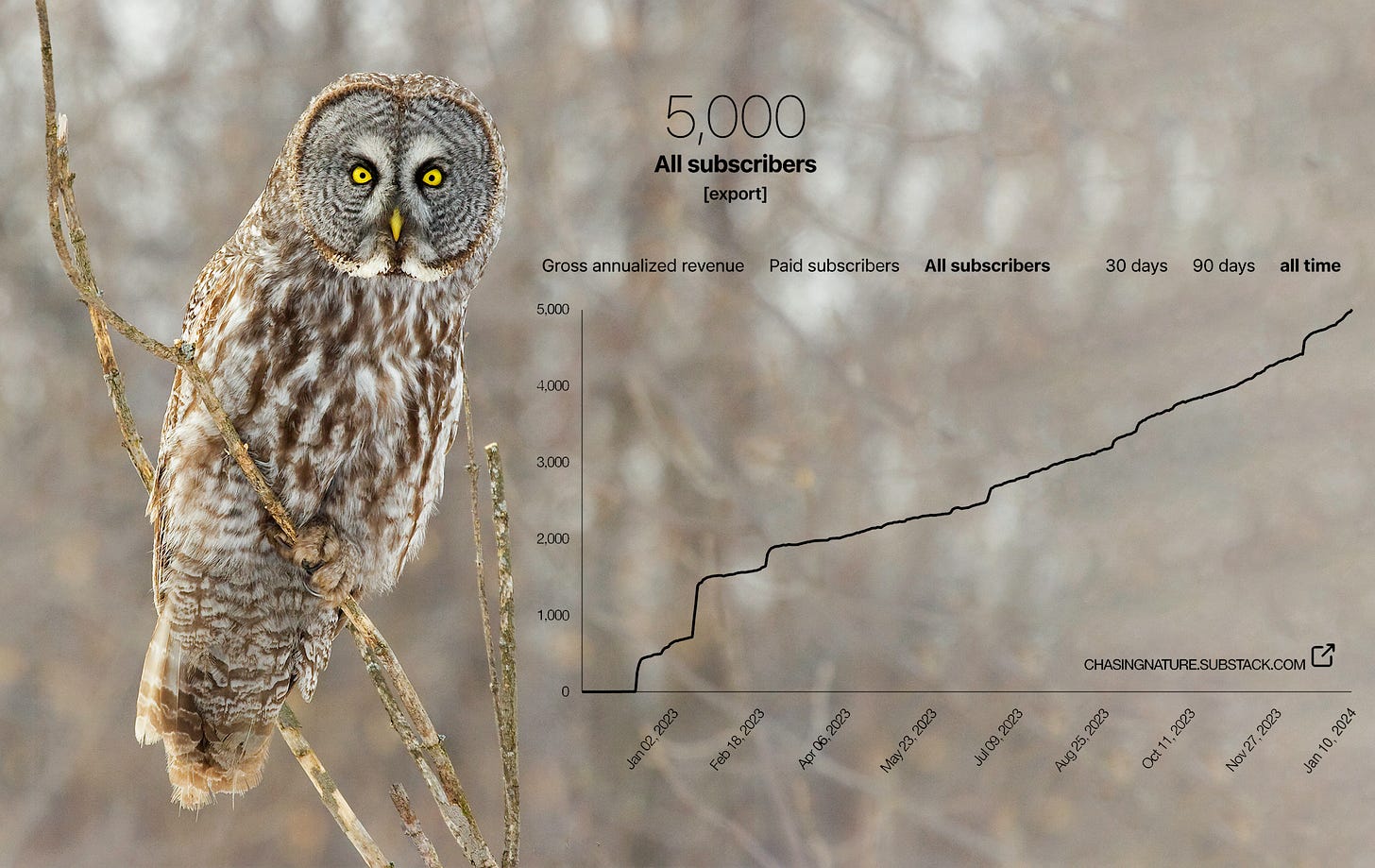

Meanwhile, in only a little more than a year, the community of Chasing Nature readers reached 5,000 on January 10 (and we’re still growing). Your being here means so much to me — I lose sleep over not disappointing you. By way of thanks, here’s a Great Gray Owl (and our celebratory Substack subscriber graph).

References

Acoca-Pidolle, S., Gauthier, P., Devresse, L., Deverge Merdrignac, A., Pons, V., and Cheptou, P.-O. 2023. Ongoing convergent evolution of a selfing syndrome threatens plant–pollinator interactions. New Phytologist. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19422

Ballard, Harvey E., Kartesz, J.T., and Nishino, M. 2023. A taxonomic treatment of the violets (Violaceae) of the northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society, 150(1): 3–266.

Bishop, Sasha G. D., Chang, S.-M., Baucom, R.S. 2023. Not just flowering time: a resurrection approach shows floral attraction traits are changing over time. Evolution Letters, Vol. 7, Issue 2, April 1, 2023. https://academic.oup.com/evlett/article/7/2/88/7072662

Wagner, David L., Grames, E.M., Forister, M.L., and Stopak, D. 2021. Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Vol. 118, No. 2, January 12, 2021. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2023989118

Lovely piece, and fascinating research. It's a bit chilling to see that the pansies are managing to reproduce but in the process of dong without insects, are making themselves inhospitable to them so that it'll become a vicious cycle. "Selfing" is such a telling word - can't help thinking it reflects the current state of humans--more alone, less in-person community. In any case, it's good to draw attention to the importance of insects in our world. Thank you.

Nature is sexy and rough as it meets the needs of the day. We are in a time of change. Compassion and appreciation of the other should rule. We can choose. Your writing makes for easy to understand yet it challenges the reader. Thank you.