Owls are alluring and captivating, especially the white owls, the Snowy Owls, which since the American election have been flying in force from the Arctic to the northeastern and midwestern United States. So it might have been fitting for me to begin this week’s dispatch with a Snowy Owl.

I begin instead with a potted plant. Like many of us this time of year, the plant, a sundew in my living room, has been reaching toward the scarce, angled light of autumn. And somewhat like the owl, my Fork-leaved Sundew (Drosera binata) is a carnivore. Rather than hunting small mammals in open country, the sundew in its pot lures unwitting insects to its sticky, glimmering tentacles (glandular trichomes).

Otherwise, the owl and the sundew ostensibly have little in common. Never will a Snowy Owl naturally meet up with a Fork-leaved Sundew, which is native to Australia and New Zealand (and cultivated by folks like me who fancy carnivorous plants).

And yet I can unite them here in prose and ideas.

Until I began keeping carnivorous plants, I’d had a field naturalist’s fondness for them in the wild. I wrote in March, for example, about my finding imperiled Venus Flytraps (Dionaea muscipula) in their only remaining swath of native habitat on the planet. Upon encountering most any pitcher plant species (in the genus Sarracenia), I often peer inside its death-chamber for doomed insect prey. And because I’m partial to dragonflies, I’ll confess to liberating a few bluet damselflies from a sundew’s fateful entanglement.

As for my potted flytraps, sundews, and pitcher plant, I left them outdoors this summer to carry out their carnivory upon Vermont insects. They did reasonably well fending for themselves in the yard. But my relationship with these plants began to change once I brought them indoors this autumn and commenced to feed them live insects. With forceps in hand, delivering flies to my plants, I’ve discovered a kind of intimacy I hadn’t expected — something more than what might come from, say, watering or pruning. I’m somewhat reluctant to admit this, but it feels like nurturing. (To the extent they’re sentient, however, I suspect the flies might beg to differ).

Although I have never been a parent, I’ve hand-fed orphaned birds and helped to raise a puppy. So I’ve exercised a few of those emotional muscles. I also like to think that my exuberant and reverent kinship with the natural world, expressed here at Chasing Nature, is itself an affirmation of that kind of nurturing — and inspires the same among readers. I just never thought I’d feel it beside a plant on my living room table.

What seems to be lacking from this “relationship,” of course, is reciprocity. A potted plant only returns what a potted plant does: grows, flowers, stays green in winter. We might expect reciprocity from the Snowy Owls now descending into the U.S. and southern Canada. But we won’t necessarily find it, at least not at first glance. I alluded to this two years ago in Chasing Nature’s inaugural post titled “Arctic Owls on a Warming Planet:”

Perched on a rocky point along the coast of Maine, the Snowy Owl is languid, indifferent, a predator without country. The wind and cold and crashing waves do not matter. You do not matter. The Snowy Owl cares not that you have driven halfway across winter to witness a white bird alone on the headlands.

So as you peer through binoculars and watery eyes at a creature from a place far wilder and colder than Maine, the owl fixes its gaze out to sea, where it might snatch a duck from the waves for a meal. But then you curse the wind chill or stomp your frozen feet. The owl spins its head your way.

From a Snowy Owl’s eyes the Arctic speaks. Hypnotic and seductive, like bioluminescence or romance, the glow brings you immediate pleasure. From the intensity of this gaze you cannot look away. And yet from the owl there really is no reciprocity.

The Snowy Owl is not like you or me. It has no interest in killing and eating you. And even if it suspects that you yourself might want to kill and eat it, the owl decides that you are, for the time being, standing at a safe distance. So it is done with you. And in that moment before it turns its gaze back toward the sea, back to its thoughts and desires, the Snowy Owl sends you a message: “Go about your business. I’ve got mice and voles and ducks to kill here. Go lead your quiet life.”

Nurturing and reciprocity, of course, come most of all from other people — at our core we’re social animals. We need each other most in times of hatred and war and other injustices (which is basically all the time). Still, there is plenty of nurture and reciprocity for us in nature, if only we would stop abusing or destroying or ignoring it; if only we might look less at our phones and with even greater awareness at what’s most genuine in the world.

I’ll find it in the authentic gaze from one of those Snowy Owls this winter or in the glimmering feathers of a Rock Dove (Pigeon) in a city park. I’ll find it among the ancient moss still green in the naked woods or there along the way in the cracked pavement. And I’ll find it out in the cold in the company of a squirrel or at home beside a little jumping spider, which I will not feed, however lovingly, to my sundew.

Postscripts

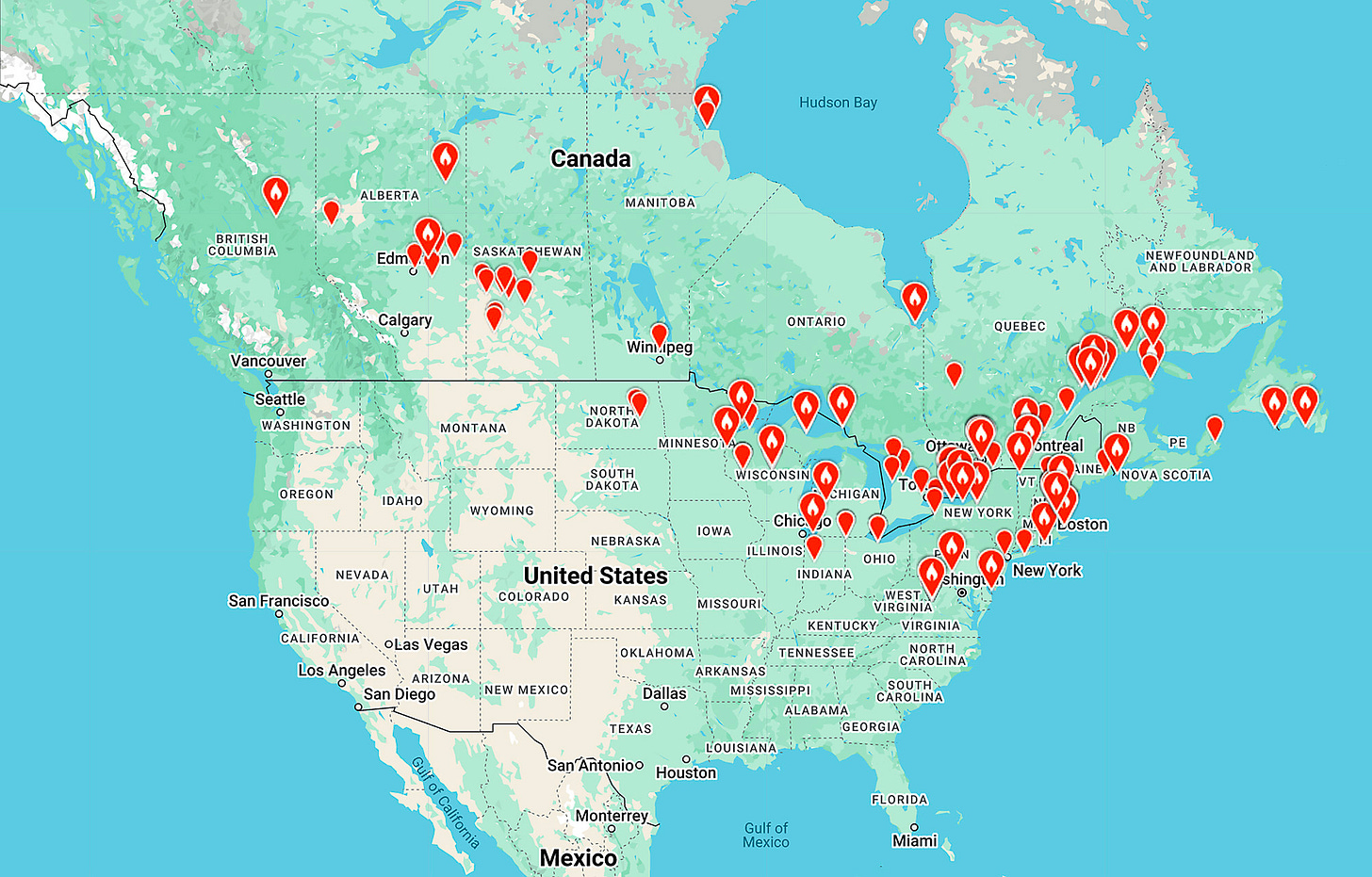

Although my Snowy Owl predictions didn’t quite pan out last autumn (but did result in a confessional essay), this November’s southbound flight is looking quite good. If you’re a paying subscriber to Chasing Nature, send me your whereabouts in an email and I might be able to send you toward one of those white owls. First consult the current sightings map below, which I’ll be updating for paying subscribers this winter in our Go Wild portal.

Also for paying subscribers, I’ve just launched a Substack Chat where we can share with one another whatever we might be nurturing or simply enjoying in nature so far this autumn (or this spring in the Southern Hemisphere).

Finally, and not incidentally, when it comes to feeding and caring for orphaned birds, and recognizing the ephemeral gift of existence, no one knows this nurturing and writes more insightfully and beautifully about it than

at here on Substack.

"How the hell is he gonna do it?" wonders Marvin. "How is he gonna make Snowy Owls and Sundews make sense together?"

Then Bryan reaches out a butterfly netter's muscled arm, "Here, hold my beer." he says, grinning.

Look I want to spend less time on my phone but I couldn’t stop reading this 🙌